Ty Cobb tried to steal home 99 times, including the one time he was successful in the World Series.

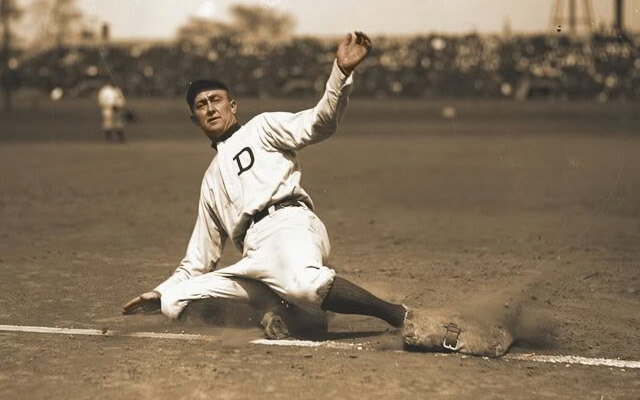

On April 20, 1912, Ty Cobb christened Frank Navin’s new $300,000 ballpark by scoring the Detroit Tigers’ first-ever run at Navin Field. He did it in typically dramatic style, swiping home in the bottom of the first inning against Cleveland’s Vean Gregg. It was the first of a record eight steals of home the Peach would pull off that summer.

Pilfering the plate was a specialty for Cobb, who retired with a then-record 892 stolen bases in 24 big-league seasons (1905-28). During his career he stole home 54 times (plus one World Series theft), far outdistancing runner-up Max Carey, who had 33 during his 20 seasons with Pittsburgh and Brooklyn. To put Cobb’s feat in perspective, consider that the two players who moved ahead of him in career steals, Rickey Henderson (1,406) and Lou Brock (938), stole home only seven times between them.

Conventional wisdom holds that stealing home should be attempted with a poor hitter at the plate because a weak hitter is less likely to drive in the runner from third. Moreover, that batter should be right-handed so as to obscure the catcher’s view of the runner.

But Cobb, a master of “small ball,” turned baseball logic on its ear. Records show he was more likely to break from third with Bobby Veach—a left-handed hitter who was one of the game’s most productive RBI men—at bat than any other player. “Cobb was using the element of surprise,” a writer noted after one of the Peach’s successful swipes. “No one thought he would try for home with a left-handed hitter up.” Which, of course, is exactly why he did it.

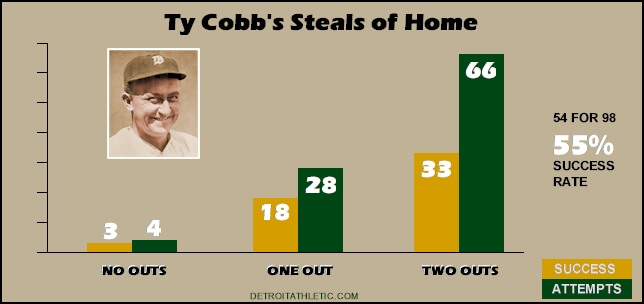

There are some interesting aspects to Cobb’s attempted steals of home. He was successful on 54 of 98 dashes for home (not counting the World Series swipe), an overall success rate of 55%. Of these 98 attempts, fully two-thirds of them—66—occurred with two outs. He was successful on these all-or-nothing attempts 33 times, exactly half.

Cobb made an additional 28 attempts with one out and was successful 18 times—a commendable 64% success rate.

Cobb was far less adventurous when perched on third with none out. Attempting to steal home in such a situation has always been considered a bad tactic. Why risk having the first out of the inning occur at home plate? But Ty was successful three of the four times he tried it.

Analyzing Cobb’s attempts further, we find that he was far more likely to pilfer home with his team ahead (28 steals in 53 attempts) than with his club behind (14 steals in 27 tries). With the score tied, he was able to dramatically deliver the go-ahead run 12 of 18 times. He also was more aggressive in the early innings, stealing 24 of 46 times in the first three innings of a game. From the seventh inning on he was more responsible, with 14 steals in 19 attempts—a sterling 74% success rate.

No player will ever approach Cobb’s record for stealing home. For starters, it’s no longer the deadball era, where runs came at a premium. Today’s big-bang offense has cheapened the importance of a single tally, and modern teams are smarter about defending against the maneuver. Third basemen play closer to the bag, while pitchers long ago abandoned the windup in favor of the set position. Both reduce the big lead a runner needs to get a jump on the ball as it’s being delivered to the plate.

Additionally, in this era of astronomical contracts, few base stealers are willing to risk a career-ending injury through a home-plate collision. For these reasons, this once-popular offensive maneuver is virtually obsolete. This particular record of Cobb’s is as safe as his .367 lifetime batting average and twelve batting titles.