On Dec. 10th, the Baseball Hall of Fame’s Modern Baseball Era Committee will decide whether Jack Morris will be inducted into the Hall of Fame.

Next month at baseball’s winter meetings most fans will be waiting to hear about trades involving their favorite team. Eyes will be on the 30 general managers and their entourages as they work the phones and slip away to meetings to finagle deals to reshape their teams. Most fans will be salivating at the news that drips out of the “hot stove league.”

But not me.

My focus will be on a fairly small, somewhat obscure committee that will meet somewhere in a hotel in Orlando during MLB’s annual winter meetings on December 10th.

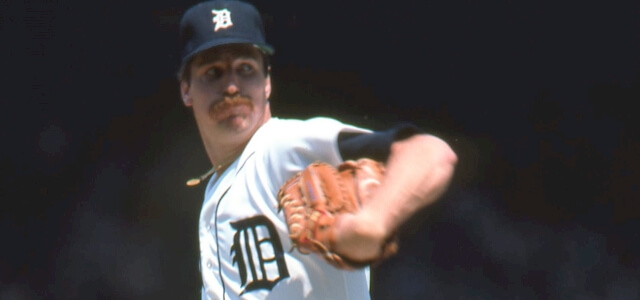

The committee is formally named the “National Baseball Hall of Fame’s Modern Baseball Era Committee.” Their purpose is to decide the fate of ten candidates for election to the Baseball Hall of Fame. Two of those candidates are of special interest to this writer: Jack Morris and Alan Trammell.

The Hall of Fame defines “Modern Baseball” as the era from 1970 to 1987 and candidates are supposed to be players who made their primary contributions in that time period. Morris pitched for Detroit from 1977 to 1990, while Trammell was an infielder for the team his entire career, spanning 20 seasons from 1977 through 1996.

Morris and Trammell starred for the Detroit Tigers in the 1980s and were key members of the 1984 team that led from wire-to-wire and captured the World Series title in exciting fashion. The ’84 Tigers are considered by most historians to be one of the best single-season clubs ever, a complete team that charged out to a record 35-5 start and finished off the competition by winning eight of nine in the postseason. Yet, the 1984 Tigers are one of the few championship teams to never have a player inducted into the Hall of Fame. Of teams to win the World Series from 1903 to 1996, only the 1981 Dodgers and the ’84 Tigers have failed to have at least one player elected to the Hall of Fame.

That footnote could change for the Tigers if either Morris or Trammell receive at least 12 votes from the Modern Baseball committee in Orlando next month. In the baseball writers’ voting, Morris received more votes (in excess of 3,200 in 15 years) than any man never elected by that voting body. Trammell also spent the maximum 15 years on the writers’ ballot, gradually building support to more than 40 percent, but falling short. Tiger fans are wondering if this more select voting bloc will see fit to finally honor one of their heroes.

Given the support Morris received through the BBWAA process (he finished second in voting twice and routinely out-polled others who were eventually elected), I’d say his chances are better than even. But the Hall of Fame’s veterans committees and era committees have been notoriously stingy. Rarely have they elected a player who did not get overwhelming support by the writers. The committee seems to feel their job is to hold up the mistakes of the BBWAA, not correct them.

Still, if anyone is going to be elected next month after that committee sits in session in Orlando, Morris has as good a chance as any. None of the other eight players on the ballot (one spot is taken by former union leader Marvin Miller) ever received as much as 45 percent support via the BBWAA.

I believe there are five men on the ballot who deserve election, but I’m only concerned with Morris for this article. More on the others later.

With that, here are five reasons Jack Morris should be elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame:

1. Every era has an ace

The Baseball Hall of Fame honors the best. Looking at baseball history as a continuum from the 1870s, the Hall has inducted every pitcher who was the most effective, durable ace of each decade. Let’s look at them:

1870s — Albert Spalding

1880s — Tim Keefe

1890s — Cy Young

1900s — Christy Mathewson

1910s — Walter Johnson

1920s — Lefty Grove

1930s — Carl Hubbell

1940s — Bob Feller

1950s — Robin Roberts

1960s — Sandy Koufax

1970s — Tom Seaver

1980s — ?

1990s — Greg Maddux

2000s — Randy Johnson

Your mileage may vary. Maybe you would choose Warren Spahn for the 1950s, or Steve Carlton for the 1970s. Perhaps you prefer Hal Newhouser to Feller in the war-split 1940s. Doesn’t matter: all of those pitchers listed above and the others I mention in this paragraph are in the Hall of Fame.

What do they share in common? They each won more games during that respective decade, started more games (in most cases), and completed more games than almost anyone else. All of them were important pitchers in pennant races and the postseason too, at least for one season, but most did it several times. (Save for perhaps Walter Johnson, who didn’t get a chance to pitch in a pennant race and Fall Classic until the 1920s.)

That was Morris too. He started more games, completed more, won more, pitched more innings, and starred on more pitching staffs that won pennants, than any other pitcher of his era. In most cases it’s not close either. Here are his margins over the next man on these statistical lists for the 1980s:

Games Started: +1

Complete Games: +31

Innings Pitched: +115

Wins: +22

Morris completed three times as many games as Nolan Ryan did in that era (133 to 44). He pitched 800+ more innings than Ron Guidry and about 400 more than Fernando Valenzuela. He started 44 more games than Bert Blyleven, pitching 360+ more innings than him, and posting nearly an identical ERA for the decade. The two were separated by four years in age, but were contemporaries for more than a decade in the same league. Morris won 58 more games than Blyleven in their 13 years in the league together. Morris did pitch for better teams than Blyleven, but his winning percentage compared to his team is only slightly below that of Blyleven.

2. The best pitcher of the new five-man rotation era

Maybe you don’t like to split eras into decades. Maybe the decade thing seems forced. Fine, then look at where Morris rates for his era. Take 1969 (the second expansion) to 1994 (the year the wild card was instituted and just as the steroid era was about to explode). Morris ranks very high in all categories, finishing near or ahead of other pitchers who are in the Hall.

Expanding our sample of pitchers to a 26-year span adds several great pitchers who began their careers in the 1960s, and a few who started in the early 1980s. But Morris holds his own against them.

From 1969 to 1994 (call it the Pre-Steroid era), Morris was:

7th in wins

11th in games started

9th in complete games

10th in innings

Here’s a complete list of the pitchers who rank ahead of him in at least one of those four important categories:

Nolan Ryan, Steve Carlton, Don Sutton, Bert Blyleven, Phil Niekro, Tom Seaver, Fergie Jenkins, Jim Palmer, Gaylord Perry, Frank Tanana, Tommy John, Jerry Reuss, and Rick Reuschel. That’s 13 pitchers, nine of whom are in the Hall of Fame. And each of those nine Hall of Fame pitchers spent part of their career in a four-man rotation, which assisted them greatly in accumulating starts and wins. Morris pitched in a five-man rotation his entire career, except for a few months in a few seasons in the early 1980s when Sparky Anderson skipped the fifth spot to get him more starts.

Was Morris as great as Tom Seaver? No. But he wasn’t just a Rick Reuschel type either Nope, Morris was the best starting pitcher of the first 10-12 years of the five-man rotation era. He averaged 34 starts in his peak years, while Seaver, Ryan, Sutton, and the others averaged about 3-5 more starts per season. Those extra 45 starts over the course of a career are the difference between 300 wins and the 254 victories that Morris finished with.

3. The post-season résumé

Morris is the author of the greatest post-season start in baseball history, measured by importance and performance. The details are legend: Game Seven of the 1991 World Series, the Braves and Twins in Minnesota; Morris vs. John Smoltz. The veteran ace versus the young gunslinger. Morris was making his third start in nine days, having beaten Atlanta in Game One and holding them to one run in six innings in Game Four. In Game Seven, Morris refused to be scored on, defusing threats along the way to a tense 10-inning 1-0 shutout victory. The performance improved Morris’s career post-season record to 7-1.

While one start (even in Game Seven) shouldn’t qualify a pitcher for the Hall of Fame, the full body of his post-season work is a strong point in favor of Morris. In 1984 he threw two complete game wins in the World Series and won his only start in the ALCS. In 1987 he had a rocky start in the ALCS against Minnesota, but came back to post a 2.23 ERA in five starts as he went 4-0 in the 1991 post-season for his hometown Twins. He started four games for the Blue Jays in the 1992 post-season and performed poorly, but his team still managed to win the World Series. He ended up 7-4 with a 3.80 ERA in 13 post-season starts. He was tapped by his manager to toe the rubber for Game One six times in October, and his teams were 8-5 in his starts, despite his struggles in that final playoff year with Toronto.

Morris was the ace on three World Series champions and won four rings in all. He’s the only starting pitcher to have never played for the Yankees or Dodgers to win four World Series titles as a regular member of the rotation.

4. The championship narrative factor

Nearly every championship team in baseball history has at least one Hall of Fame player. The object of the game is to win, and great players make that happen. Morris was the best pitcher on one of the best teams of the last 50 years (the ’84 Tigers), and one of the best teams in a single season ever.

Cooperstown should honor the best players on the best teams, the players who have the greatest careers and the most impact on pennant races. Morris was that pitcher for the ’84 Tigers and he was important on two other World Championship teams too.

5. He was famous and did famous things

It’s the Baseball Hall of Fame not the Baseball Hall of Stats. While I think Morris has the statistical record to merit election based on that alone, he also has several non-stat factors working in his favor.

Morris did famous things. He was a famous and important player of the 1980s and early 1990s. For a dozen years he was the ace of several great teams, he started the All-Star Game three times, he started crucial games in the pennant race. He was on the big stage, whether it was an exciting last weekend start against the Brewers to decide the second half division title in 1981 when he was 26, a complete game victory over the Blue Jays in the final week of the ’87 season when he was in his prime, or Game Seven of the World Series in 1991 when he vanquished one of the aces of the next generation in a classic duel. He started Game One of a postseason series six times. He pitched a no-hitter (on national TV). He set a league record for most starts on opening day.

The trendy pitch of the 1980s was the split-finger fastball. Some people called it a forkball. Bruce Sutter rode that pitch to the Hall of Fame as a reliever. Morris was taught the pitch by pitching coach Roger Craig. Morris threw it effectively longer than any starting pitcher, utilizing it so well that it tumbled down out of the strike zone, resulting in lots of strikeouts. He helped popularize the pitch, which transformed the game of that era.

Morris finished in the top five in Cy Young voting five times, and in the top ten seven times. He got MVP votes in five different seasons, for three different teams. Seven weeks into the 1984 season he was 10-1 and on pace to win 30 games, something that caused buzz throughout the game. He pitched eight complete games of more than nine innings, the highest total of any pitcher who started his career after 1971. He tossed 161 pitches in the start after his no-hitter in 1984, though he lost a tough luck game 2-1. He regularly threw 130+ pitches, one of the last pitchers to put his arm through that. Yet he took the ball start after start, the consummate pro.

Morris was a strong personality (albeit a grumpy one) on great teams. He never mellowed during his playing days, but that cantankerous image made him one of the most fascinating figures of his era. His competitiveness was unsurpassed.

On the fame scale, Morris rates ahead of many pitchers in the Hall already. Don Sutton didn’t personify his era like Morris, he wasn’t a #1 starter for most of his career. Bert Blyleven didn’t pitch as many big games. Nolan Ryan wasn’t on the big stage as much. Jim Palmer never threw a no-hitter. Phil Niekro and Gaylord Perry didn’t get the MVP support that Morris did. Tom Glavine never felt like an ace like Morris did. The most recent pitchers to have the swagger that Morris had on the mound are Pedro Martinez and Roy Halladay. There was something about Morris that made you watch him pitch.

I don’t know if Jack Morris will be elected by the veterans committee next month. But the time to debate his candidacy is over. The numbers are in the books. His accomplishments are legend. The baseball writers made a mistake, and the committee should correct it.

One reply on “Five reasons Jack Morris should be elected to the Hall of Fame“

Comments are closed.