It’s fitting that it took a stubborn, daring maverick to bring professional baseball to the corner of Michigan and Trumbull in Detroit.

The actions of George Arthur Vanderbeck, who was kicked out of more than one professional baseball league by fellow owners who couldn’t stand his cocky arrogance and rude manners, resulted in Bennett Park and eventually Tiger Stadium being in the Corktown neighborhood. As a consequence, many lasting memories were created for baseball fans who witnessed history at that location.

The Western League was all but dead and abandoned after it failed to complete the 1893 season, shuttering in June due to financial mismanagement by most of its members. But undeterred, representatives of the Indianapolis, Kansas City, Milwaukee, Minneapolis, and Toledo franchises met in November to consider salvaging a circuit to be played in the midwest. They voted to add three more teams, and welcomed applications for ownership. That’s when Vanderbeck’s name was mentioned by John S. Barnes, owner of the Minneapolis franchise. Barnes knew Vanderbeck from their dealings in the nascent Pacific Coast League. While Vanderbeck had a reputation for being discourteous, he was also bold and ambitious. Barnes was sure that Vanderbeck could properly shepherd a franchise in a new city.

Vanderbeck didn’t choose Detroit as much as it chose him. Born in upstate New York, he spent his early adult years in Toledo, before bolting for Oregon and then California, where he had his first taste of organized baseball. George’s father was killed in an accident after a team of horses collided with his carriage when the young Vanderbeck was still not twenty years old. His inheritance allowed him to pursue real estate ventures on the west coast, and an apparent affinity for the game of baseball, which he probably played in the hotbed of the national pastime in New York as a youth, led Vanderbeck to lease land for the construction of a ballpark in Los Angeles.

Vanderbeck was strong-willed and opinionated, which alienated him from other rich folks trying to build a Pacific Coast League in the 1890s, so he let it be known he would plant a professional team anywhere in any league that would take him. He answered the call from Barnes and accepted a franchise in the Western League to be located in Detroit for the 1894 season.

Detroit hadn’t seen a pro team since the Wolverines folded after the 1888 season. The city of Detroit had proved to be too small to support a profitable team at that time, but Vanderbeck had plans to bring in money.

Detroit’s Corktown Neighborhood

Cities take shape for all types of reasons: geography, political allegiances, race, economics, and commerce among them, with many others. One of the most famous neighborhood communities in Detroit came about because of a disease that attacked the potato. In Ireland in the 19th century the potato was crucial for survival, for many reasons I don’t have space to discuss here. A disease called blight started killing potatoes and caused The Great Potato Famine. As a result, tens of thousands of Irish people starved, and many left for (literally) greener pastures.

Many Irish migrated to the United States in the years between 1845 and 1900. Some of them went to Detroit where land and housing was cheap. Most of them settled in the western part of the city, specifically between Third Street to the east, Grand River Avenue to the north, 12th Street to the west, and Jefferson Avenue/Detroit River to the south. By 1860, Irish were the largest ethnic group in Detroit, and many of them were from County Cork in Ireland. For that reason, their neighborhood became known as “Corktown.”

When George Vanderbeck was preparing to field his new professional baseball team in Detroit for the 1894 season, he searched for affordable lots. He also wanted something near housing areas, near neighborhoods where he could draw spectators to his games. But there was a problem: Vanderbeck couldn’t secure a large enough tract of land to put in a baseball field for the 1894 season. Not on such short notice. As a result, the Detroit team played their first year in the Western League on a field located on Champlain Street (later renamed East Lafayette), between Helen and East Grand Boulevard, near Belle Isle.

But in October of 1894, Vanderbeck finally located his property when he visited a hay market located on the corner of Michigan Avenue and Trumbull. The market was uneven, soggy, and unrefined. It stunk of wet hay and mud, and the location was being used as a sawing ground for cedar blocks, and as a city stone quarry. But Vanderbeck had a vision: he would build a state-of-the-art ballpark and revitalize the Corktown neighborhood. He reportedly paid $8,250 for the land and another $10,000 to sculpt it and build a wooden ballpark on it.

Bennett Park Opens

Vanderbeck understood that he needed to market his team, so he called on a Detroit catcher named Charlie Bennett, who had starred for the Wolverines in the 1880s, and tragically lost his legs in a train accident in 1894. Vanderbeck capitalized on the Bennett’s popularity and christened his new venue Bennett Park. Every year for decades, Bennett would throw out the first pitch of the season.

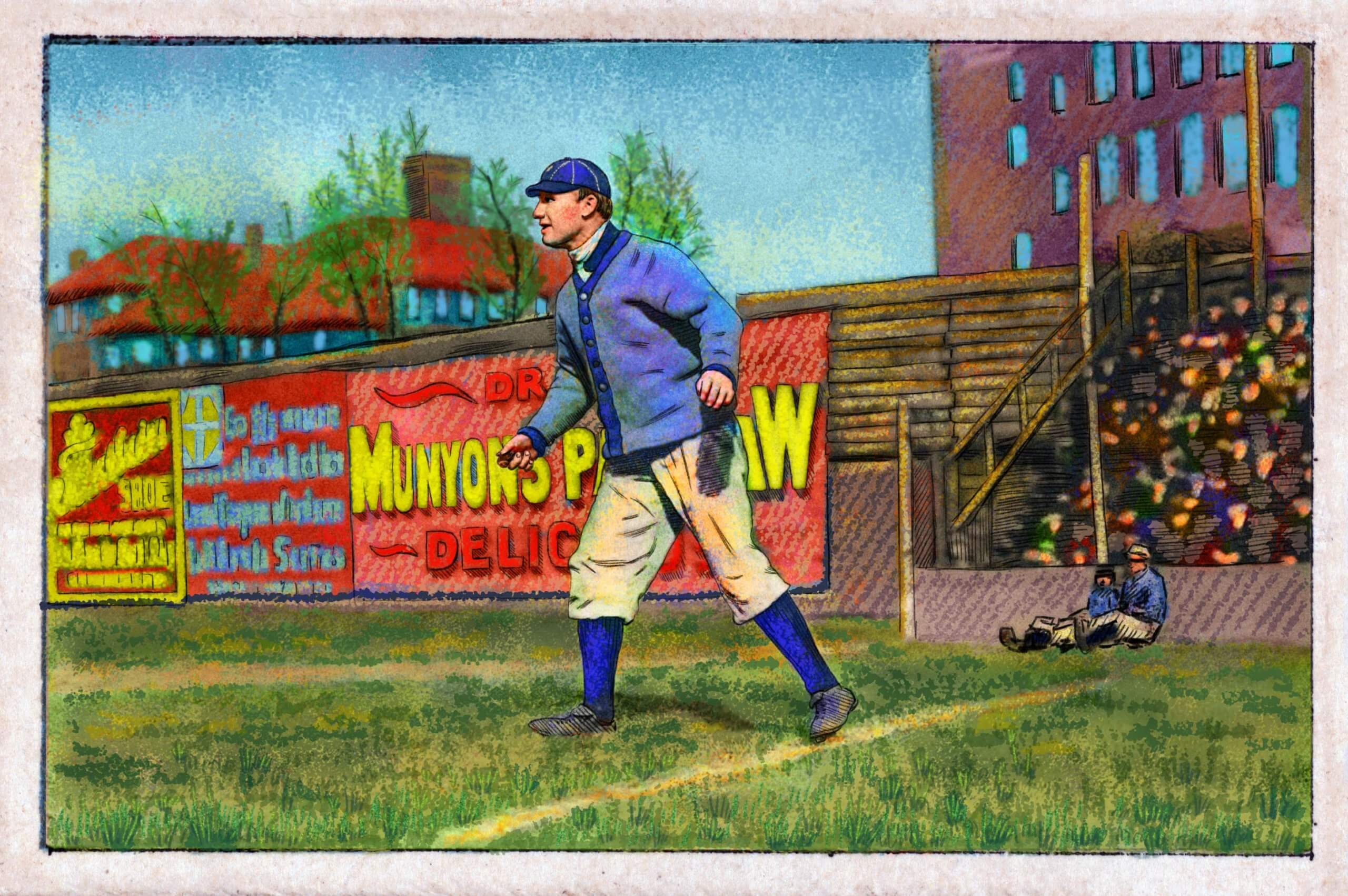

The first game played by a Detroit pro baseball team at The Corner in Corktown was an exhibition on April 13, 1896. The Tigers, as they were newly being called, defeated a local rag-tag team, 30–3 in a laugher in front of about 600 spectators who apparently didn’t get splinters from the new wooden bleachers. Baseball would be played on the site for 104 seasons.

In 1912, the wooden ballpark was replaced by a modern brick and steel venue dubbed “Navin Field” for then team owner Frank Navin. Later it was renamed Briggs Stadium, and finally Tiger Stadium. The location hosted nine World Series and some of baseball’s greatest players. Babe Ruth hit his 700th home run there, and Ty Cobb won twelve batting titles as a Tiger. The final game was played at the corner of Michigan and Trumbull in 1999.

Vanderbeck’s unceremonious exit from Detroit baseball

George Vanderbeck was a rascal, to put it politely. In fact, he proved to be a miserly, incompetent, borderline criminal owner of a professional baseball team. Although he was colorful.

Once in 1897, a Detroiter named William Gordon, who made his home next to Bennett Park, complained that errant baseballs were breaking his windows. How did Vanderbeck reply? He bought Gordon’s property and doubled the rent. Vanderbeck also consistently had trouble making his payroll and refused to pay contractors for work they did around his ballpark. One season a dispute with a laundry company over payment forced the Tigers to wear soiled uniforms for weeks.

Other owners in the Western League had troubles with Vanderbeck too.

“One thing that struck me forcibly was the perfect unanimity with which the Western League magnates don’t like their Detroit colleague — Vanderbeck,” wrote W.A. Phelon, Jr. in The Sporting Life. “[Vanderbeck] has been responsible,” Phelon wrote, “so they say, for 90 percent of all the league’s troubles and difficulties; he has been invariably turned down, and yet keeps on troubling.”

Things got bloody for Vanderbeck in 1899 when Detroit Free Press sports editor Bo Needham demanded he be paid the money he was owed for serving as official scorer for that season. The Detroit owner balked, promoting Needham to punch Vanderbeck in his “vander-beek” several times.

Finally, saddled with debts and facing a messy divorce, Vanderbeck sold the team in March of 1900 to a local saloon operator and former prize fighter named James D. Burns.

“After having aired his affairs in the papers for many weeks and tried in every way to defeat his wife in her attempts to secure alimony, he is no longer a magnate,” The Sporting Life wrote of the sale. “Had he taken the advice of his friends and not tried to beat his wife out of everything, or had he acted fairly and kept a few of the promises which he made, he could have settled his domestic affairs and might still own the Detroit Club and franchise. Now he is out, and among the other American League magnates there will be no regrets, for he was thoroughly disliked and distrusted.”

Vanderbeck remained in Detroit for many years, but eventually relocated to California. He never again owned an interest in a baseball team. The man who built the first ballpark at the famous Corner in Detroit died at the age of 73 in 1938, only days before opening day.