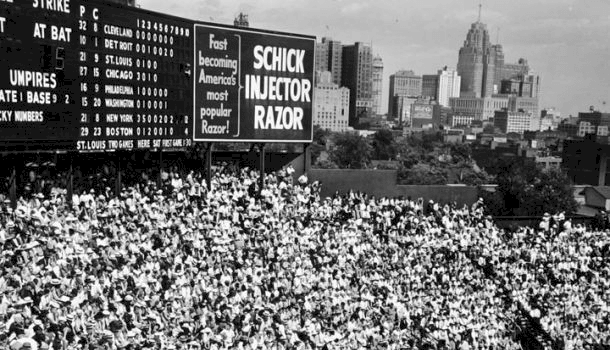

Fans crowd into the center field bleachers at Briggs Stadium in Detroit for a Fourth of July doubleheader in the 1950s.

There was a time when July 4th meant a lot of baseball.

The fourth of July doubleheader was a tradition across Major League Baseball until well into the 1960s. But for the fifth consecutive season there won’t be a scheduled doubleheader in baseball this year.

Baseball doesn’t play two any more, not like they used to. The reasons are many: (1) players don’t like it (2) owners aren’t willing to forfeit gate receipts (3) the labor union has negotiated them away (4) venues are in higher demand (5) the games are too long (6) pitching staffs are stretched thin (7) baseball has much competition for entertainment.

There are probably a half dozen more reasons that I haven’t thought of. But suffice to say, the doubleheader is gone and won’t likely be coming back soon.

Until the mid-1960s, most baseball teams scheduled at least three doubleheaders each year: Memorial Day, July 4th, and Labor Day. For some teams there were other events (the Red Sox hosted two games on Patriot’s Day in Boston for decades, one game in the late morning, the other in the afternoon).

Because of the mode of travel (train mostly) until the 1950s, teams needed more days off for travel. A doubleheader gave them a chance to schedule more days off. In 1939 the St. Louis Browns played enough doubleheaders that they had 37 days off during the season. In 1943 the Chicago White Sox played 44 doubleheaders, 58 percent of their schedule.

The current CBA (Collective Bargaining Agreement) ensures that players get 21 days off a season, or about 3-4 per month. The season is 183 days long, and they need to get 162 games in there somehow.

MLB owners earn an average of $1.5 million every time they host a game. They’d lose that for a traditional doubleheader with one ticket for both games. Ironically, it was the allure of “two games for the price of one” that led to the invention of the doubleheader in the first place. The term comes from the double counting of heads for the two games.

Most teams used to have a traditional rival on July 4th for their doubleheader. The Yankees and Red Sox frequently squared off. The Tigers and Indians met 27 times in the 56 July 4th doubleheaders played by Detroit between 1901 and 1963. The Browns and White Sox played eight straight July 4th twinbills, and the Athletics often squared off against the Senators. Seeing that the two leagues only had eight teams each, four July 4th doubleheader traditions were easy to figure out. The Giants and Dodgers once even played a “home and home” doubleheader.

Fans in most cities embraced the 4th of July tradition, filling the ballpark on what was typically a day off. Because games were usually played in a brisk two hours or less, doubleheaders meant you were at the ballpark for about five hours, with twenty minutes between games. For many it was their best chance to see baseball in person. Holiday doubleheaders were events in some cities, like Boston, New York, and St. Louis.

Bill Veeck was famous for his July 4th celebrations. As owner of the Cleveland Indians he tried almost everything: giving red-white-and-blue straw hats to every man who entered the ballpark; ballpark employees dressed as our founding fathers; giving out copies of the Declaration of Independence; and fireworks. The maverick owner never met a promotion he didn’t like, and if he had fans in his ballpark for two games over the course of five or six hours, Veeck wasn’t going to miss the chance to entertain and market to them.

In their 56 scheduled Fourth of July doubleheaders the Tigers didn’t have great success. They were swept 14 times and only swept their opponent eleven times. Each year from 1917 to 1919, the White Sox swept both ends of the July 4th doubleheader from Detroit. 29 times there was a split, and twice the Tigers lost one game and tied the other. In the era before lights, if the second game of a doubleheader went a little long and no one was ahead, it would be called a tie. In their next to last scheduled July 4th twinbill, in 1962, the Tigers lost both games to the Indians in Cleveland on walkoff hits. The following year in their last Independence Day doubleheader, Detroit swept the Twins at Tiger Stadium.

What killed the doubleheader? The easy answer would be the labor union. In the 1960s when Marvin Miller took over control of the Major League Baseball Players’ Association (MLBPA) he fought hard for the rights of his players. As a result, more days off were added to the schedule and fewer doubleheaders. Modern travel allowed teams to play more single games with the same or more days off.

But the real reason doubleheaders were abandoned was economics. The owners realized that more single games meant more gate receipts, of course. But with the advent of television contracts, they also recognized that more games meant more programming for the networks and more money in their pockets. Why play doubleheaders and have say 78 home game broadcasts when you could have 81 broadcasts to sell advertising on?

After the loss of the holiday twinbills, baseball still scheduled some doubleheaders, though far fewer. For a few years baseball tried to schedule doubleheaders on the Sunday the week before the 4th of July, but that effort soon was abandoned.

Not since 2011 has MLB scheduled a doubleheader on purpose. Otherwise, every doubleheader in the last eight years has been as a result of a rainout or scheduling difficulty.

Some in the game have called for the return of the doubleheader to baseball. The thinking is that with just six doubleheaders (one per month), the season could be reduced by one week. That would mean the World Series could once again be the “Fall Classic” instead of the November Winter Wonderland. Given the economics of the game, it’s hard to see baseball doing such a thing, however.

One reply on “When baseball played doubleheaders on the 4th of July“

Comments are closed.