Baseball is an imitation game. All sports are. Once you show you can have success shooting threes or using a run/pass option offense, other teams will copy it. In the early 1980s, a new pitch was the rage in baseball, a pitch that Bruce Sutter was using with phenomenal success out of the bullpen. They called it the forkball because the index and middle fingers surrounded the baseball on either side, like the tines of a fork. That pitch, also related closely to the split-finger fastball (or splitter) was completely responsible for Sutter being in the Hall of Fame, and also helped Jack Morris get to the same place.

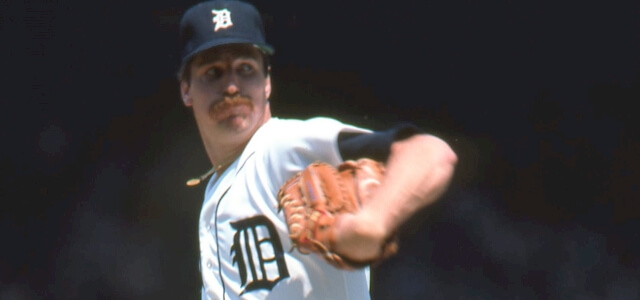

Before he learned the forkball from teammate Milt Wilcox in 1982, (who had been in the Cubs’ organization with Sutter in the 1970s), Morris relied on a fastball, slider, and a pretty bad changeup. With the forkball, Morris had a pitch that complemented his fastball and made him very difficult to hit against because he was able to use the same art slot for the pitch as he did his breaking ball.

“A forkball actually comes out of your hand with the rotation of a curveball,” Morris explains. “Because of the pressure on your fingers, there’s no way you’re going to have the same velocity you do with your fastball, therefore it’s kind of like an offspeed curveball. Once I learned how to keep it down, and literally bounce it at times, a hitter couldn’t sit on both. He couldn’t sit on a fastball and a forkball. It’s a devastating pitch.”

Catcher Lance Parrish became expert at handling the pitch. “The way [Morris] threw it, it came out like a fastball then it fell, like it was dropping off a table,” Parrish said. “I can’t count how many batters walked away shaking their heads at that goofy pitch.”

Mike Scioscia, catcher for the Dodgers, called it “the pitch of the ’80s,” and it helped many pitchers achieve success, including Mike Scott, who won the Cy Young Award in 1986. Ron Darling, David Cone, and Randy Johnson also used the pitch effectively.

Less than two years after learning the forkball, Morris had the pitch going very well in his second start in April of 1984 at Comiskey Park in Chicago. It was a Saturday afternoon and the game between the Tigers and White Sox was on national television. Morris had his forkball dropping so much that day that he walked six batters, walked the bases loaded early in the game. The pitch was bouncing in front of catcher Lance Parrish, but Morris had such good stuff on it that he escaped trouble. He carried a no-hitter into the seventh, the eighth, finally the ninth inning. The White Sox barely got the ball past the mound, bounced grounders to first or back to Morris. He struck out a few guys and got his no-hitter, the first by a Detroit pitcher in more than two decades. Morris later estimated that he threw 40 percent forkballs in the game.

The Detroit pitching coach for most of the years Morris was with Detroit was Roger Craig, who loved the forball (or split-finger fastball as some called it). Craig was sort of the Yoda of the forkball, teaching it to any pitcher who would listen. Dan Petry became a pupil too and it made Detroit’s #2 starter one of the better pitchers in the league in the early 1980s. But Morris was his star pupil.

No pitcher in baseball started more games, completed more games, pitched more innings, or won more games in the 1980s than Morris, who used his forkball as a critical part of his repertoire. Later, in the seventh game of the 1991 World Series, pitching in a scoreless game with the runners on the corners, Morris went to his favorite pitch to escape the jam, striking out Ron Gant in the fifth. In the eighth when the Braves had the bases loaded with one out, Morris dropped a forkball on Sid Bream, who grounded into an inning-ending 3-2-3 double play. Eventually Morris tossed ten scoreless innings and won the game 1-0 to clinch the title. And that “goofy pitch” was key to his success.