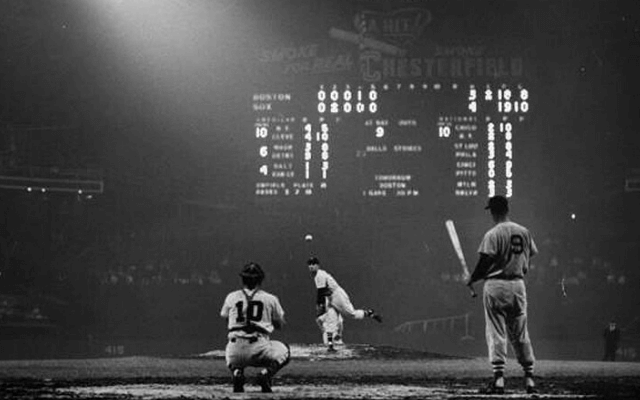

Ted Williams prepares to bat at Comiskey Park in 1959. By this time, the White Sox were using lights on the large center field scoreboard to signal pitches to their batters.

Few things are as entertaining as righteous indignation. Boy, do we have a lot of that right now in baseball.

In light of an alleged sign-stealing operation that included a center field camera, a TV monitor, and of all things, a trash can, the Houston Astros are in the cross hairs. Winners of two of the last three American League pennants, the plucky Astros are taking a hit in the respect column, and the righteous indignation gang is hot on their heels.

There are folks who want the 2017 World Series title taken from the Astros. They either want it handed to the NL champion Dodgers, or vacated. As if this were the NCAA. Oh lord help us if Major League Baseball starts emulating the NCAA.

Sign stealing by use of electronic devices is prohibited by MLB. The rules are not well-written, and I suspect the Astros will escape a terrible punishment because the rules afford them enough wriggle room to claim “We didn’t know!” But hard and fast rules are coming, no doubt.

But regardless of what happens to the Astros, TrashCanGate will take its place next to SpyGate and DeflateGate as one of the most controversial scandals in modern sports history. There will be a large segment of sports fans who won’t think any punishment is harsh enough, and another group will build conspiracy theories that are sure to populate hours of video time on YouTube. Yeehah!

Place me in a different category. I think this “scandal” is fun. It’s one of the first fun scandals we’ve had in sports in decades. For once we’re not talking about athletes shoving syringes in their butts or people paying bribes to sign foreign talent, or “boosters” giving jobs (and sacks of cash) to teenage recruits to play basketball at their alma mater. Stealing signs is the jaywalking of sports crimes.

This isn’t even the most fascinating case of sign-stealing using electronic means. The most infamous happened more than sixty years in the 1950s. Remember the 1950s? Those were supposed to be the innocent days of America, when young men who played sports were good, upstanding Americans with pomade-slicked hair, clean faces, and honest intentions.

A future Hall of Famer helps Chicago use their electronic scoreboard to steal signs

The most efficient and longest-running sign-stealing operation in baseball history was masterminded by George Kell. You recall, George, don’t you? The gentleman from Arkansas, the hard-hitting third baseman who won a batting title in Detroit, the man with the kind voice who started every Tigers’ broadcast with “Hello everyone, I’m George Kell.” The man who added four syllables to the word “Tuesday.”

It was George Kell, along with a teammate on the White Sox, who devised a sign-stealing system in Chicago that was in place when the ChiSox won the 1959 pennant. A system that was still being used in Comiskey Park two decades later.

The Tigers traded Kell, a fine third baseman, to the Boston Red Sox in the middle of the 1952 season. The Tigers were not a good team back then. Their best hope was to be mediocre, and on most days they didn’t achieve that. Kell was one of the best players at his position, but Detroit needed more help than one man could provide. The Sox sent five players to the Tigers in a deal for Kell.

In Boston, Kell continued to hit over .300 and play great defense at the hot corner. While he was there he tried to fill a void left by Ted Williams, who had been called back to the Marines to fly jets in the Korean War. He also learned some tricks in Beantown.

The Red Sox had a sophisticated sign-stealing operation that they used in Fenway Park. Usually, the previous days starting pitcher (or a member of the bullpen) would climb inside the scoreboard on the famed Green Monster (the wall in left field) and relay signs to the batter. Often, an arm or a towel or a plain red card sign on the scoreboard would indicate the pitch. When he changed socks and was dealt to Chicago in the middle of the 1954 season, Kell didn’t want to miss out on knowing which pitches were coming.

“The guys in Boston opened my eyes,” Kell said in an interview late in his life. “I was with the White Sox for only a week when [general manager] Frank Lane started asking me what I learned in Boston.”

Kell was reluctant to snitch on his former team, but he figured the White Sox were signing his checks, so he owed his loyalty to them. The veteran infielder explained how the Red Sox were stealing signs. He even went further: telling Lane that the White Sox could do something similar.

“Bob Kennedy was my backup [at third base],” Kell explained, “and we talked a lot. We came up with a system we thought would work.”

In the 1950s, Comiskey Park had one of the first electronic scoreboards in baseball, and it was the largest scoreboard too (if not the largest, pretty damn close). The ballpark had been renovated in the late 1920s, with the addition of two sweeping upper decks of seats. But the decks only extended to left and right center, leaving a gap in center field where a giant scoreboard was located. In 1951, the White Sox added electricity to that board. By 1954 when Kell joined the Sox, the scoreboard offered a perfect opportunity for espionage.

Kell and Kennedy worked with Lane and the ballpark staff to implement a system where the scoreboard operators would flash a light for a type of pitch. A team employee (often Kennedy initially) would sit in the scoreboard with binoculars and get the signs from the catcher while the White Sox were at bat, relaying them to the scoreboard operator sitting next to him.

The White Sox sign-stealing, designed by Kell, worked brilliantly. In the two years prior to the system being put in place, the White Sox played far better on the road. But in 1955, with the lights flashing the pitches to eager Chicago batters, the team reversed that trend and won more than 63 percent of their games at Comiskey.

Kell was nearing the end of his career and the White Sox traded him in 1956, but the scoreboard sign-stealing operation remained in place. When Bill Veeck bought the team in 1959, he was delighted to learn of the system. That season the Sox won the pennant, and the following April when Veeck unveiled a modern “exploding” scoreboard he made sure to leave room for the green and red lights that signaled fastball or curve to his batters.

Over the years many opposing teams knew about the White Sox and their prying eyes inside the scoreboard. Even into the 1980s, teams were sure that a weird light was being triggered to signal pitches. By that time, Kell was the lead broadcaster on television for the Tigers. He probably knew what the White Sox were doing better than anyone else. After all, George came up with the idea.

Some baseball fans are up in arms right now about the sign-stealing scandal down in Houston.

But to me seems like the same gamesmanship baseball has always had.

There’s an old saying in the game: “If you’re not cheating, you’re not trying.”

Now that we’re reminded of an electronic sign-stealing operation from the 1950s, we have to remember this: the more things change, the more they stay the same.

4 replies on “George Kell designed an electronic sign-stealing operation more than 60 years ago“

Comments are closed.