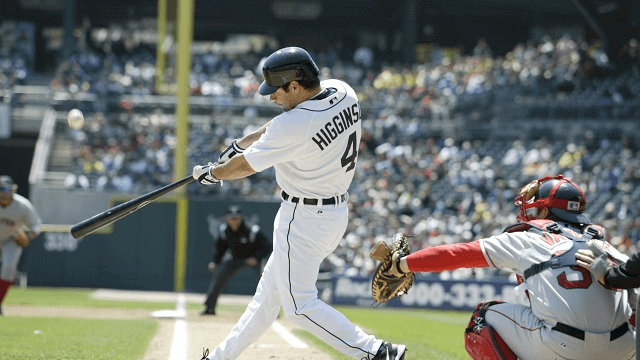

Bobby Higginson’s short left-handed swing was productive for the Detroit Tigers in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

It was the best of timing. It was the worst of timing. It was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness. It was the era of post-Sparky, it was the era of a new ballpark. It was the season of light, it was the season of darkness. It was the spring of hope, it was the summer of despair.

When was it? It wasn’t a Dickens’ novel (that intro paraphrases the opening of A Tale of Two Cities for those of you who slept through English Lit 101). Nope, it was Tiger baseball in Detroit in the 1990s, and one of the most intriguing protagonists of that era was Robert Leigh Higginson, aka Bobby, aka Higgy.

It really was the best and worst of timing for Higginson. On one hand he benefited from the transition the team was going through in the mid-1990s, which opened several spots in the lineup. But he also ended up playing on losing teams year after year after year as a member of the Tigers. In more than a decade with the club, Higginson never played on a winning team and the closest he came to first place was 16 games. Perhaps no player in modern baseball history toiled for so long without ever playing a single meaningful game after Labor Day.

He wasn’t supposed to be a star. He was drafted by Detroit off the campus of Temple University in the twelfth round in 1992. Higginson was a Philly kid with a bit of big city Philly swagger, but he wasn’t your prototypical physical specimen. When compared to other Detroit prospects like Tony Clark and Phil Nevin, Higgy looked like a runt. But he had something special.

Ironically, had Sparky’s tenure in the dugout lasted longer, Higginson might have never blossomed at all. Sparky was notoriously tough on young players, especially those who didn’t fit his mold or tow the line. In ’95, Higginson played for the gray-haired skipper as a rookie. He got off to a fine start, popping five homers in his first 23 games and ten by the All-Star break, but once the scouting report got around the league that he was a low fastball hitter, the outfielder struggled to a .224 finish with only four homers after the break. Sparky “retired” after the season and Higginson found an important ally the following spring in new manager Buddy Bell. Whereas Sparky may have never tolerated Higgy’s uneven temper, Bell stuck with the youngster in his sophomore season. He put together an excellent second year, batting .320 with 35 doubles, 26 homers, and 81 runs batted in. Also promising was his knowledge of the strike zone: the lefthanded hitter walked 65 times and struck out only 66.

Even though he was still fresh in the big leagues, Higginson realized his fortune in finding a home under the wing of Bell.

“No one wants to be a platoon guy,” Higginson told the Detroit Free Press. “Sparky didn’t want young guys playing against all kinds of pitching, but Buddy gave me the opportunity.”

For years after his rookie campaign, Higginson would be less than glowing in his assessment of Anderson, a man who never paid much attention to the rookie other than to ride him hard. Higginson was never much for instruction.

But Bell didn’t always have it easy with Bobby either. In 1997 he guided the young Tigers to a 26-game improvement, but Higginson wasn’t always a peach to deal with. Bell told the Free Press: “[Higginson] can be his own worst enemy, he takes the good too good and the bad terribly.”

Indeed, at times throughout his career Higginson showed how contentious he could be when faced with adversity. He pouted when he didn’t play well, barked when he disagreed with a call from the home plate umpire, and had a few run-ins with teammates, most notably Juan Gonzalez, who probably deserved it. Tellingly, despite working his way up the ladder of tenure with the club, Higginson never became a team leader. He was what they called in the 1950s, a “clubhouse lawyer.”

Belying his “average joe” physical stature (he was two inches below six-feet tall and never looked as hunky in a uniform as teammates Clark, Juan Encarnacion, or Gabe Kapler), Higgy put up solid numbers for the Tigers in the late 1990s and early 2000s. He hit between 25 and 30 homers four times in a five-year stretch and twice went over the century mark in RBIs. Still, he never made an All-Star team for a couple of reasons. First, as a corner outfielder he was up against some stiff competition in the American League. And second, he didn’t seem like an All-Star. Higginson always seemed like an overachiever. Sure, he was a threat in the middle of the lineup, but he wasn’t a guy you built a team around, even one as terrible as Detroit was.

A valuable part of his game was Higginson’s play in the outfield. Not since Al Kaline’s heyday had the Tigers boasted such a fine right fielder with the glove and arm. On three occasions he led the AL in assists, both because his arm was strong and accurate but also because opposing teams liked to challenge him. Again, he didn’t look like he could throw that well.

There were a few big days. In 1997 in a game against the Mets at Tiger Stadium, Higgy blasted three home runs. His third homer went high and deep into the upper deck in right. Three years later he hit the trifecta again, blasting thee homers in Cleveland against the Indians as he also drove in six runs. He had a five-hit game against the White Sox, and on September 27, 1998, Higginson entered the game as a pinch-hitter with two outs in the ninth and hit a home run to spoil a no-hit bid by young Toronto pitcher Roy Halladay.

After the age of 30, Higgy’s power faded fast, at least partly due to the team’s move from Tiger Stadium to spacious Comerica Park. His short lefthanded stroke was now hitting fly balls to the warning track instead of over it. His last full season came in 2004 when he played for Alan Trammell, a former teammate and the sixth manager to write Higginson’s name on a lineup card in Detroit. When the front office wooed Magglio Ordonez during the offseason, Higgy saw the writing on the wall: he was no longer needed. The following spring he made the ballclub but Trammell made it clear that the veteran would fighting for playing time with Craig Monroe as the team’s outfield reserve.

A few weeks into the ’05 season, Higgy was miserable. He was a shell of his former self, having a tough time getting around on fastballs that he used to swat to right field. The team owed him $9 million so it wasn’t likely that they’d send the veteran down to Toledo or release him. Fans were merciless, showering the 34-year old with boos after every failure. Trammell did not start Higginson on opening day and gave Bobby only four starts in April. On May 5th, after going 0-for-21 while playing in only eight games in nearly for weeks, Higginson walked upstairs to the office of general manager Dave Dombrowski and retired. His eleven-year career was over.

A few days after taking off the Detroit uniform for the last time, Higginson bought a full-page ad in the Free Press and thanked the fans for their years of support. It was a classy move from a player who was loved by many in the first half of his career and then became a favorite punching bag toward the end.

It wasn’t Bobby Higginson’s fault that the Detroit Tigers stunk from 1995 to 2005. It wasn’t his fault that the formerly solid organization hired and fired a slew of managers. That the new owner, Mike Ilitch, allowed Randy Smith to run his baseball operation into the ground while his hockey team was winning titles. It certainly wasn’t Higgy’s fault that he wasn’t Magglio Ordonez or Kirk Gibson, that he was a good player who had some really good years but was never a superstar. It wasn’t his fault that the team abandoned Tiger Stadium and wore that ugly new logo for a few years in the 1990s. But like Grant Hill with the Pistons, Higginson found himself stuck like a magnet to a period of Detroit sports history that most fans want to forget. He didn’t make an All-Star team, he didn’t win a Gold Glove, he didn’t help the team to the playoffs or even as many as 81 wins. He didn’t win a darn thing.

But if he’d come along earlier, when Trammell and Sweet Lou Whitaker were in their prime and the Tigers were contenders, or later when Jim Leyland was priming the team into a pennant favorite, history would probably remember Higginson more favorably. Still, his career with Detroit is one of the most interesting in franchise history.