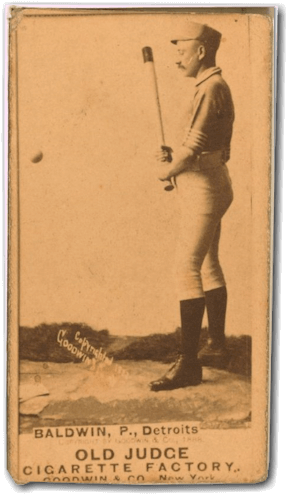

This Old Judge baseball card from the 19th century shows Detroit pitcher Charles “Lady” Baldwin doing something he wasn’t known for – batting.

Unlike many of his 19th-century contemporaries, Charles Baldwin didn’t smoke or chew tobacco, drink liquor, cuss, or visit whorehouses. Naturally, Detroit’s star southpaw of the mid-1880s was nicknamed “Lady.”

In his prime, he was one of the toughest pitchers ever to toe a big-league slab. Ned Hanlon, who patrolled center field at Recreation Park behind Baldwin, once said: “He had wonderful command, speed and curves, and knew how to work the batters.”

Baldwin was born in 1859 on a farm near Buffalo, New York, and moved to Michigan as a boy. He played ball for the local town team in Hastings, where his catcher was Dan “Deacon” McGuire, his future teammate in Detroit. In 1883, Baldwin turned pro as a member of the Northwestern League, first with Grand Rapids and then Milwaukee.

In 1885, Baldwin was acquired by the Detroit Wolverines, a weak club that finished sixth in the National League that season. Despite a so-so 11-9 record, Baldwin averaged fewer hits and walks and more strikeouts per nine innings than any pitcher in the league.

Detroit’s fortunes turned around the following year when the Wolverines acquired the “Big Four,” a quartet of stars led by future Hall of Famers Dan Brouthers and Jim “Deacon” White. That summer, Baldwin turned in one of the greatest seasons ever enjoyed by a lefty. In leading the resurgent Wolverines to a second-place finish, he completed 55 of 56 starts, pitching 487 innings while compiling a 42-13 record with a 2.24 ERA. In addition to his league-high 42 victories—then a record for lefties and still the second-best season total ever for a southpaw—he topped the National League in shutouts (7) and strikeouts (323).

Those were mind-bending numbers even for that era, but Baldwin paid a heavy price. In 1887, Detroit’s mound ace struggled to post a 13-10 record. At one point he was 6-9 and was sent home for a month to rest his sore shoulder. Meanwhile, the Wolverines made short work of the rest of the league, never spending a single day out of first place as they captured the pennant. In the ensuing 15-game cross-country “world’s series” with the St, Louis Browns of the American Association, Baldwin flashed his old stuff, winning four of five decisions as the Wolverines claimed the city’s first major-league championship.

That was Baldwin’s last hurrah. He pitched only six games in 1888, going 3-3 with a godawful 5.43 ERA. After a year away from the game, he tried coming back in 1890 with Brooklyn of the short-lived Players’ League. He split his time between Brooklyn and Buffalo, recording a 3-5 record before being released in July.

Baldwin’s burned-out arm caused him to retire at age 31. Once among the game’s best-paid pitchers, making $3,000 a year, he was content to return to Michigan, where he worked the fields and tended his orchard. He later got involved in real estate. When the old southpaw died in 1937, the golden anniversary of the Wolverines’ championship season, the Sporting News eulogized: “To this day, the old-time fans of Michigan tell their children about the marvelous feats performed by the great Lady Baldwin.”