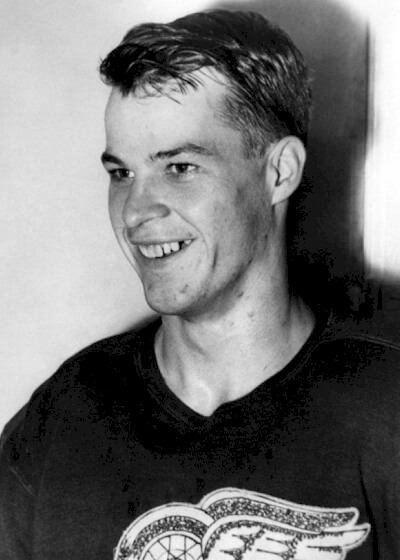

Gordie Howe started his career with the Detroit Red Wings when he was 18 years old.

There’s no debate, certainly not in these parts, that the greatest player in hockey history was a slope-shouldered lad from Saskatoon named Gordie Howe. And there’s certainly no dispute anywhere that Gordie is a marvelous human being, someone admired for his courage, humility, decency, droll wit, and common touch. But long before he became the celebrated “Mr. Hockey,” Gordie was just another hungry kid from the Canadian prairies. It was that desperate childhood that forged Gordie into the athlete and man he famously became.

Gordie was born March 31, 1928, in Floral, Saskatchewan, a nondescript town nine miles east of Saskatoon. “That place is so flat,” somebody once said of Saskatoon, “you can sit on your front porch and watch your dog run away for three days.”

Gordie was one of nine children born to Ab and Katherine Howe. It was a hardscrabble life of deprivation, poverty, and daily struggle. The family drank powdered milk and often ate oatmeal three times a day. The house, which Ab had bought for $650, had coal-burning stoves and little else. Insulation consisted of wrapping drafty windows with plastic and stuffing felt into the cracks. There was no running water. The family used a 45-gallon drum of water that was kept on the porch and brought inside when it was cold. The children usually bathed at school instead of home.

“The biggest fear I had when I joined the Red Wings,” Howe later said, “was that somebody would come and see where I lived.”

In Saskatoon the temperature often dropped to 20 or 30 degrees below zero. Snowstorms sometimes blocked the entire front of the Howes’ house. “We’d have to go out the back and try to dig through the front door,” Gordie recalled in his autobiography.

“You’d kick out about seven or eight feet of snow. It was amazing. You know, I look back and I think, those were hardy people who established their homes out there. People used to walk to work in a blizzard.”

Gordie got his first skates when he was four. A neighbor lady, destitute and desperate, came by the house with a sack filled with odds and ends that was selling in hopes of feeding her baby. “I didn’t have much to offer,” recalled Gordie’s mom, “but I reached into my milk money and gave her a dollar and a half. We dumped the contents of the sack onto the floor. Out fell a pair of skates. Of course Gordie pounced on them.”

Unfortunately, his sister Edna also pounced on them. Each emerged with one skate, several sizes too big. They put on several stockings until they fit, then went outside to try out their new treasure. One-legged skating soon lost its appeal for Edna, who after a week finally surrendered her skate to Gordie for a dime.

Gordie got his even temperament and charitable disposition from his mother (who had given him the dime) and inherited his looks and dry humor from his father. Ab Howe, a hard-bitten sort of few words, went through life with a flask in his pocket. “He said it was in case of snakebite,” Gordie explained. “So, every once in a while, he’d yell ‘Snakebite!’ and take a snort.”

Once Gordie’s father went fishing with a friend, had a few belts, then managed to capsize the boat. While the friend swam away to get help, the senior Howe hung onto the boat for all he was worth. After a half-hour he finally let go—only to have his feet hit bottom. The boat had capsized in three feet of water.

As a youngster, Gordie could skate for miles on the frozen roads and gullies around his house. Although hard times forced him to wear discarded equipment that had been fished out of the garbage and repaired (including his jockstrap and cup), he felt “like a million dollars” whenever he jumped onto the ice. “We could play hockey al day,” he said. “Imagine a 12-hour game. You’d play all day, go home and eat, come back and say, ‘Who’s winning?’”

Growing up in the middle of the Great Depression helped the boy develop self-reliance. Gordie trapped gophers for a penny a tail, delivered groceries, caddied at a nearby golf course, and caught fish and sold them for 5 or 10 cents apiece to the local Chinese restaurant.

As a teenager, he worked pouring concrete sidewalks with his dad. He could lift five 95-pound bags of cement at once, grabbing them kitty-corner from a bended-knee position, then swinging around and throwing them into a wagon. “My dad would always brag about how much I could lift,” he said, “so I could never embarrass him by dropping the bags.” Gordie’s pride resulted in a hernia operation when he was still young, but the strenuous work accounted for the herculean strength in his hands, wrists, shoulders, and arms.

By the time he was 15, Gordie was making a name for himself as an all-around athlete at King George School. He was already 6 feet tall and close to 200 pounds. He never grew much after that, playing most of his professional career at between 195 and 205 pounds.

He wasn’t much of a student, handicapped by what was later diagnosed as dyslexia. Some boys teased him by calling him “doughhead.” None of this prevented him from carefully practicing his penmanship. He was certain that one day he would be asked for his autograph, and he wanted to make sure that when he signed his name it would be neat and legible.

When Gordie was 15, he was invited to a New York Rangers tryout in Winnipeg; homesick and shy, he turned down an offer to attend Notre Dame College in Wilcox, Saskatchewan, on a scholarship.

The following year, 1944, a Detroit scout named Fred Pinckney invited him to a Red Wings camp in Windsor. Pinckney bought him his first suit of clothes for the trip. Wings coach and general manager Jack Adams was impressed with what he saw and arranged for Gordie to work out with the junior club in Galt, Ontario. As part of the bargain, Adams promised to get him a Wings jacket.

“I wanted that jacket so bad all the time I was in Galt,” Howe recalled. “I remember that quite a few times I walked down to the railroad station by myself. I knew when the Red Wings’ train would be coming through town traveling to games. I’d just wait there for them. I figured that if they stopped for anything, I’d go aboard and see if I could ask Adams about my jacket, but the train never stopped. They went rolling on through every time. I’d just walk back home.”

Howe never attended high school in Galt, as was originally planned. Instead he found work in a defense plant. In September 1945, he was invited to camp with the Wings. World War II was coming to an end, but the housing shortage forced him to bunk at Olympia Stadium, where he amused himself by killing rats with his stick. After scoring two goals in an exhibition in Akron, Ohio, he signed his first professional contract to play for the Wings’ farm club in Omaha, Nebraska. There he scored 22 goals and saved $1,700 of his $2,700 salary.

The following September, he reported to the parent club’s training camp. After learning he would stay with the Wings, he cautiously approached Adams about some unfinished business.

“Mr. Adams,” he said, “it has been two years now and I haven’t got my jacket yet.”

Adams had more important things on his mind, but he wasn’t about to lose his young prospect over a $17 jacket. He sent Howe to a sporting goods store downtown and told him to sign for it. Teammates Ted Lindsay and Marty Pavelich accompanied the youngster. “It was smooth like satin on the outside,” Gordie remembered, “with leather sleeves and an alpaca lining. It had a big ‘D’ with ‘Red Wings’ written on it. It looked like the most beautiful jacket in the world.”

Howe made his NHL debut on October 16, 1946, in the season opener against Toronto. Adams put the rookie right winger on a line with Syd Howe and left winger Adam Brown. Here was irony. A few years earlier, Gordie had fished Beehive Corn Syrup labels out of his neighbors’ garbage and mailed them to the manufacturer in return for pictures of NHL players. His favorite, because of the name, was Syd Howe. Unfortunately, Gordie got stuck with far more pictures of Toronto goalie Turk Broda.

Lo and behold, who should be in the nets that evening at Olympia but Broda, who in the second period of a 1-1 tie earned the distinction of surrendering the first of Howe’s 801 regular-season NHL goals.

After Gordie scored, he thought to himself, “Okay, now I’m registered in the record books.” Then Brown skated over and deadpanned, “You didn’t get that, I got it.”

The two argued until Brown started laughing. “Oh geez,” the relieved rookie said. “I was gonna go to the president of the league! That was my goal!”

In the final period, Howe got the crowd going again with a body-check that knocked Leafs captain Syl Apps out of the game with a twisted knee. “Gordon Howe is the squad’s baby, 18 years old,” observed the next day’s Detroit News. “But he was one of Detroit’s most valuable men last night. In his first major-league game, he scored a goal, skated tirelessly and had perfect poise.”

Gordie’s burning ambition was to stay with the varsity. Like most untested players, he had a two-way contract that called for a substantial pay cut should he be farmed out—from $7,500 to $3,500. This was incentive enough to do well.

The problem was getting ice time. He was used sparingly and didn’t pot his second goal until nine games later. It took another 11 games before he scored his third goal. Veteran Joe Carveth gave the anxious youngster some advice. Carveth “warned me not to be surprised if I didn’t too well the first half of the season, that things would work out better in the second half, when I settled down. He was right.”

Howe’s gifts were subtle. He appeared almost laconic as he glided down the ice in long, powerful strides, shrugging off opponents as he moved the puck from his forehand to his backhand. He could seemingly stickhandle forever. His greatest weapon was a blistering wrist shot, which was most deadly within 15 to 20 feet of the net.

Although still a teenager, Gordie was a major physical force on the ice. In his very first NHL game he lost three teeth—curiously, the only teeth he would spill in league competition. “After that,” he said, “someone had to come through lumber to get me.”

Gordie finished his first NHL campaign with 7 goals and 15 assists for 22 points before going scoreless in the five games he played in the ’47 playoffs.He also started a near-riot at Olympia in a semifinal game against Toronto. He and the Leafs’ Gus Mortson started brawling inside the penalty box, which in those days was shared by the guilty from both teams. Fans joined in. The police finally restored order, but not before the fighting had spilled over into the aisle and one spectator had pitched a chair at Mortson.

After the 1946-47 season, Adams stepped down as head coach after 21 seasons. Tommy Ivan, who had coached Howe at Omaha in 1945 before taking over the farm club in Indianapolis, moved behind the Detroit bench.

One of Ivan’s first moves was to put Gordie on a line with Ted Lindsay and Sid Abel. The trio clicked right from the beginning, and soon the “Production Line” was adding hardware to the Wings’ trophy case. In his sophomore season, Gordie also switched numbers. As a rookie had had worn No. 17. Now he wore the soon-to-be-iconic No. 9 on his jersey.

Only 19 years old, Mr. Hockey was on his way.