Forty years ago at the baseball winter meetings, Detroit Tigers general manager Jim Campbell sat a table with John McHale, his counterpart for the Montreal Expos. The two baseball men talked players, doing the dance that execs do when they want something but they don’t want to show how much they want it.

Earlier that day, when he briefed manager Sparky Anderson on his meeting schedule, the two men discussed the Expos’ roster, pouring over the names. They were looking for pitching, and when Sparky ran his finger down the Montreal roster and came to the name SCHATZEDER, he stopped. The grey-haired skipper liked Dan Schatzeder, a 24-year old lefthander coming off a fine season. Sparky told Campbell that if the Expos indicated Schatzeder was available, he should pursue a trade.

But McHale made it pretty clear to Campbell that Schatzeder was not on the trading block, and the two men continued down their rosters to discuss other names. When they got to Ron LeFlore, Detroit’s speedy All-Star center fielder, Campbell didn’t rule him out, which caused McHale’s eye brows to raise.

“I was surprised when they mentioned him,” McHale said. “Other teams had inquired about Schatzeder but we told them he was untouchable. Then Leflore’s name came along and we had to listen.”

While McHale imagined LeFlore hitting balls into the gaps on the fast artificial turf of Olympic Stadium and stealing oodles of bases in the red-white-and-blue uniform of the Expos north of the border, he and Campbell finalized the trade. The Tigers got a much needed southpaw for their rotation. Injuries had decimated the Detroit rotation in recent years, leaving few options.

“We had to come out of the winter meetings with a lefthanded starter,” Anderson said. “That was our main goal, but we knew how hard it would be to get one.” Sparky was happy that his thoughts on the young Montreal lefty had nudged his boss.

“I’d like to think that my input, my thoughts on Schatzeder, had a lot to do with the deal,” Anderson said.

Indeed it had. Since accepting the Detroit job the previous June, Anderson had raised the bar of expectations for the Tiger organization. He’d also quickly sized up his clubhouse, and he knew who he wanted to stay, and who he needed to get rid of.

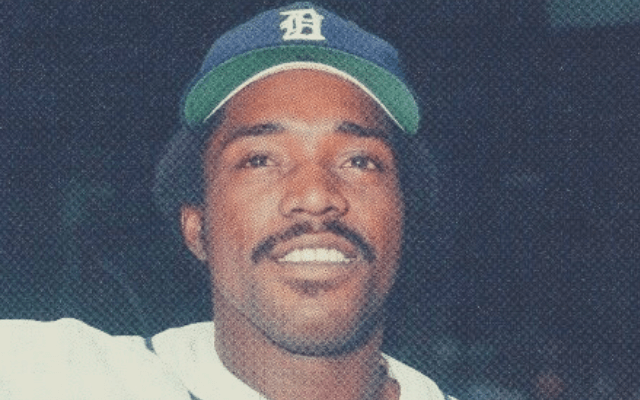

LeFlore had been signed out of Jackson State Prison when he was briefly released for a tryout with the Tigers in 1973. He was batting leadoff for the Tigers 14 months after his release from prison, and he was an All-Star starter two years later. He grew up on the tough streets of Detroit (quite literally), and he was a dynamic player. He was strong, a high-average hitter, and he could run like a deer. In 1978 he stole 68 bases. When he got on base at Tiger Stadium, fans chanted “Run Ron, Run!” In 1978 a made-for-TV movie was released about his life, starring LeVar Burton. So trading LeFlore was a big deal.

But to Sparky it was a necessity, and his prescient views on LeFlore turned out to be valuable for the franchise.

After the 1980 season, LeFlore would be a free agent, and he was going to demand big money. In Campbell’s prior discussions with LeFlore and his agent, the Tiger outfielder reportedly turned down a six-year, $3 million deal. For Campbell, a conservative man who despised free agency and the rapid increase in salaries, the writing was on the wall: Detroit would probably lose LeFlore after the 1980 season.

Anderson knew the fans in Detroit didn’t like the trade, but he didn’t care. After carefully handling a tough clubhouse in Cincinnati for eight years, he intuitively knew that LeFlore was not going to be a positive presence going forward. If the Tigers were going to win a pennant, Detroit needed to remove LeFlore from their clubhouse.

LeFlore turned his life around coming out of Jackson after being convicted of armed robbery. He had made a terrible mistake, but he had been a young man, one who drifted aimlessly without a direction. The Tigers organization became his family, and his success in baseball seemed to show his maturity and growth. But there was trouble brewing, and Sparky knew it.

When Anderson arrived in Detroit in 1979, he found a mostly young team with poor work habits. He heard complainers, he saw lazy players, and he encountered losers. And that’s what the Tigers were in the late 1970s: losers. Since the stars of the 1968 champions and 1972 playoff team had aged and retired, the franchise had spiraled into a tail spin. There were promising players drifting up from the farm system, but Sparky knew those players would never grow into winners if the losers influenced them. With stardom and cash in his pocket, LeFlore was starting to gravitate to a bad crowd by 1979. Sparky was terrified what LeFlore would become if he made half a million dollars per year.

After an outstanding season north of the border with the Expos, LeFlore signed a lucrative deal with the White Sox. LeFlore was instantly a millionaire, and all that money destroyed him. In the next few years he associated himself with drug dealers, strip club owners, strippers, and just about any sort of bad seed you can imagine. Chicago was not the place for LeFlore to be.

“The worst thing I ever did was go to the White Sox,” LeFlore said during an interview many years later. “It was too close to Detroit, too close to the people I had tried to stay way from. I made my own decisions, and I made plenty of bad ones.”

The former All-Star played his final big league game in 1982, less than three years after the Tigers offered him to Montreal based on Sparky’s recommendation.

The reaction in Detroit to the deal was universally negative. Fans jammed the switchboard in the Tigers’ front office. Newspaper columnists panned Campbell and charged the team with not caring about winning.

We all know what happened in Detroit: the farm system funneled great young players to the major league team over the next few years. Kirk Gibson arrived to fill the outfield void left by LeFlore, and Jack Morris emerged as the staff ace, with young Dan Petry as his #2. Most important was the maturation of Alan Trammell, Lou Whitaker, and Lance Parrish, who served as the cornerstone of the team that won the 1984 World Series. After the 1981 season, the Tigers shipped Schatzeder back to the National League, to the Giants for a long-legged outfielder named Larry Herndon. That trade proved to be a good one for the Tigers.

Sparky Anderson never finished high school, and he was not a formerly educated man. His father had been a house painter, and Sparky could butcher the English language. But the man knew people, he had an innate ability to size people up. The Tigers made other deals, jettisoning other players, and soon the clubhouse began to reflect the values Sparky wanted. Rather quickly, the team began to win. That all started forty years ago when Sparky Anderson pushed the front office to rid themselves of a problem-in-waiting.