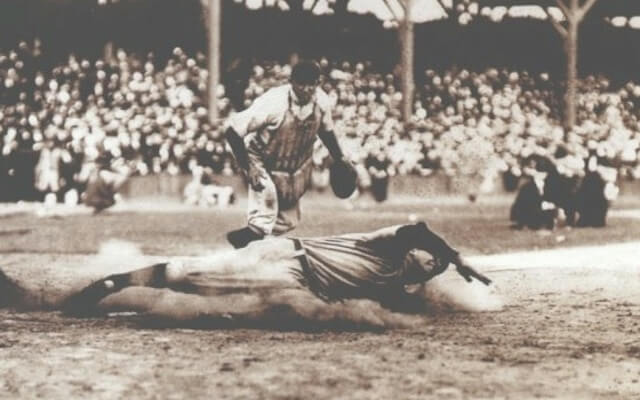

Ty Cobb slides home safely on a sacrifice fly in the eighth inning of Game Three of the 1908 World Series at West Side Grounds in Chicago. Catcher Johnny Kling of the Cubs looks on.

The last time the Cubs were champions it happened in a different world that would seem foreign to us. The ballparks were made of wood, the uniforms were wool, all of the players were white, and the ball they played with was much different.

The last time the Chicago Cubs won the World Series it wasn’t even called the World Series.

The last time the Cubs were champions of the baseball world they celebrated their victory in Detroit in front of the smallest crowd to ever see a World Series game. The muted celebration (there were no gang piles or high fives back then) happened at The Corner of Michigan and Trumbull in a city that was on the verge of exploding as the technological and manufacturing capital of the world.

The action on the field during the deadball era

The best player in the 1908 World Series was Mordecai Brown, a pitcher with a pitch that was nearly unhittable. In an era when runs were scarce, Brown was one of the best at keeping runners off base. But without the agriculture-base economy of the 19th century, Brown never would have been a ballplayer.

Brown was born in the year that American turned one hundred. When he was growing up on the family farm in rural Indiana he suffered a terrible injury when his right hand became trapped in a feed chopper, resulting in the loss of most of his index finger. A few weeks later he fell and broke several fingers on the hand, further disfiguring it because the breaks were never set properly. So much for 19th century health care.

The mangled hand served as a perfect launching pad for sharp-dropping curve balls. But Mordecai didn’t become a great pitcher immediately, he wasn’t discovered until he showed off his breaking pitch while playing in a coal mining league in the 1890s. It wasn’t until 1904, when he was 27 years old, that Brown found his way into the Cubs’ rotation. By this time he’d acquired the nickname “Miner” and also “Three-Finger” to describe the deformed right hand he used to spin his curve. But fans and teammates simply called the quiet farm boy “Brownie.”

Wearing the heavy wool uniform of the era, Brownie pitched a shutout in Game Three, dominating the Tiger lineup that featured Ty Cobb and Sam Crawford. In Game One, Brown entered in relief in the eighth inning of a one-run game and ended up getting the win. In all, Brownie pitched 11 innings and allowed just six hits and only one unearned run against Detroit.

The baseball used in 1908 was much different than the one we see today. The stitching was higher, allowing pitchers to grip the ball and perform wonderful magic tricks with it. The inside of the ball was different too, the yarn spun looser and the materials used of lower quality than would come later. As a result, the ball was said to be “dead” and was more difficult to hit for distance. But even if players could have hit the ball far, they probably wouldn’t have. In 1908 the strategy in baseball was to hit singles, sacrifice, steal bases, and play for one run. In that era two or three runs was often enough to win a game.

The Cubs were loaded with talent, led by player/manager Frank Chance, scrappy second baseman Johnny Evers, and their formidable pitching staff. Their opponents were younger, led by 21-year old Ty Cobb, one of the few players in the game from south of the Mason-Dixon Line. Cobb and his outfield teammate Sam Crawford barely tolerated each other, but they were skilled at performing hit-and-run and double steal plays.

After their victory in Game Five to take the championship, Chance had kind words for the vanquished AL flag winners:

“The Tigers, individually and as a team, are the finest lot I have ever met,” the Cub skipper told reporters, “They are gentlemen and never once during the five games of the series just closed did one hasty word pass between the two teams. I can’t help, also, but give you my hand when I say that Detroit as a ball town is a little dandy.”

Does Detroit still seem like a “dandy”” town?

The finances and landscape of baseball in 1908

This year, Cubs’ starting pitcher John Lackey will earn $16 million. In 1908, the Chicago team split a little more than $27,000 of World Series money among 20-22 players and coaches. The highest-paid player in the Cubs, player/manager Frank Chance, earned $15,000 (which equates to about $370,000 in 2016 dollars). But most players made about $1,200 a year and needed every penny to make ends meet.

World Series shares in those days were meaningful. A player could double his annual income through a postseason share check. Baseball was a good living, but most of the players weren’t rich. In fact, right after the 1908 World Series the Cubs players didn’t scatter—they traveled to California to play an exhibition series against the Pacific Coast League champions, the winning team guaranteed 75 percent of gate receipts. Members of the Tigers organized a trip to Cuba to earn more cash that winter too.

Teams were owned exclusively by white men who made their riches in industry or media. The Chicago Cubs were owned by a man named Charles Murphy, a former newspaper man who gained control of the team when he received a loan from Charles Phelps Taft, the younger brother of then vice-president William Howard Taft and a media mogul. Murphy owned the Cubs for eight years, but it was the most successful period in franchise history: the Cubs won four pennants, two titles, and averaged 100 wins per season. The Tigers were owned by Frank J. Navin, a conservative man who made his wealth as a lawyer/accountant and who was in the first of 27 years of ownership of the Detroit Baseball Club.

It never would have occurred to Murphy or Navin that there were no players of color on the field in 1908, that every man under contract in “organized” baseball was white. “Negro” players had their own leagues and white fans were not interested in seeing the races mix in athletics. It would be nearly 45 more years before a black man (Ernie Banks) would wear the uniform of the Cubs, and shamefully the Tigers didn’t field a black player until 1958.

What it was like to be a baseball fan in 1908

The final out of the ’08 Fall Classic came on a dinky little play. Detroit catcher Boss Schmidt, the biggest player on the team and a man built like a clenched fist, produced a dribbling ground ball in front of the plate. Cubs’ catcher Johnny Kling pounced on it and fired to Frank Chance at first base to record the 27th and final out of the game. Cubs win! Cubs win!

Except no one could have called “Cubs win!” because baseball wasn’t on the radio in 1908. Radio broadcasts of sports wouldn’t become popular for another two decades.

To listen to important games played out of town, fans (or “cranks” as they were known back then), would gather at newspaper offices and get updates from “callers” who were relayed information via telegraph. Some cities would post large electronic scoreboards to show the game action. This practice continued into the 1930s.

There were only 6,200 or so fans in the stands at Bennett Park on October 14, 1908. Why such a sparse crowd? Several factors combined to suppress attendance. The Cubs were playing in their third straight championship series, which at that time was called “The World’s Series,” and their fans were not exactly thrilled about the postseason tilt, a repeat of the ’07 matchup between Chicago and Detroit. In those days, the Series was relatively new, it had only started five years earlier and one season the teams refused to meet each other. Most teams already played postseason series to earn extra money, so what made the World’s Series so special? For many fans it wasn’t, and veteran fans of the National League game had little respect for the fledgling American League. To some, it seemed like a mismatch.

Another reason the stands were only half full (Bennett Park held about 12,000 at the time) was a dispute between the owners and the players over tickets. Normally, gate receipts for the first four games of the series were to be split with the players, but members of the Cubs argued that the receipts from each of the first five games should be divvied up, since Detroit’s wooden ballpark was much smaller than West Side Grounds, which could accommodate close to 19,000 fans. The owners disagreed and after a ticket-scalping scheme in Chicago resulted in a disputed gate count for Game Three, the two sides battled each other in a war of words in the Chicago newspapers. Team leader Johnny Evers reportedly suggested that he and his Cub teammates refuse to play Game Four. The resulting controversy turned off many fans in both cities, especially rooters in Chicago who might have taken the short train ride to Detroit.

Even without the off-field turmoil over money, fans in Detroit were not exactly thrilled about going to the ballpark for a Wednesday afternoon game with the Tigers down three games to one, As a result, the wooden stands at Bennett Park had patches of empty seats as Orval Overall, the tough Chicago righthander, stymied Detroit to close out the series.

If you’d been in Detroit that day you would have seen a city that was quickly emerging as a city of the future. Just two weeks earlier, Henry Ford had introduced the Model T, a marvel that would change the world. The Ford Motor Co. quickly became the largest employer in the city, the state of Michigan, the nation, and then the world. Within a few years a Model T would be rolling off Ford’s “assembly line” every few minutes and within a decade more than half the vehicles on the planet were made in Detroit.

The “World’s Series” of 1908 was the last time the Cubs were crowned champions of baseball, but as we have seen, it was a different game and a different time.