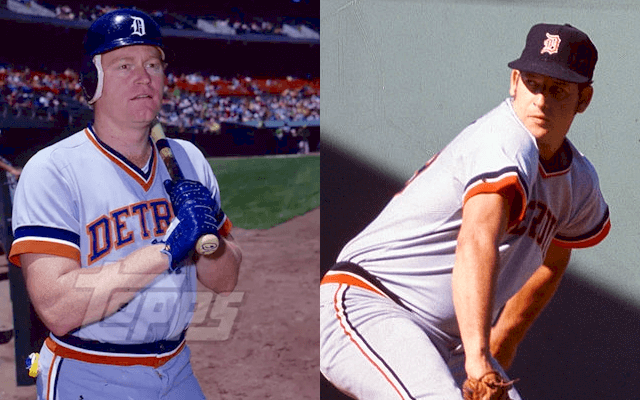

The Detroit Tigers traded pitcher Mickey Lolich (right) for outfielder Rusty Staub at baseball’s winter meetings in 1975 in a deal that was originally vetoed by Lolich.

“We’re tickled to death.”

The date was December 12, 1975, a Friday. It was late, around ten o’clock at night. A bleary-eyed Jim Campbell, general manager of the Detroit Tigers, was talking about the team’s just-announced trade.

“We got the one thing we were looking for—a real sound RBI man.”

That RBI man was none other than Daniel Joseph “Rusty” Staub.

As for Detroit, they surrendered their long-time left-handed stalwart, the former hero of the 1968 World Series, Mickey Lolich. From now on, the pitcher would be calling Shea Stadium home. He was off to play for the New York Mets.

The deal had been more than 24 hours in the making. Long-distance phone calls (ask your parents, kids) between Campbell and Mets GM Joe McDonald produced a preliminary deal in the wee hours of the morning. Lolich, however, being a 10-year veteran, had the right to veto the deal.

Lolich woke up Friday morning to the bad tidings: After 17 years in the Tigers’ organization, the only one he had ever known, he was being shown the door.

But Lolich did not want to leave the Motor City. He wanted to finish his career there, so he balked at the deal.

Campbell and McDonald, fearing it was back to the old drawing board, contacted Robert Fenton, Lolich’s attorney. Together, the three of them went to work on trying to change The Mick’s mind.

It took a lot of cajoling, a lot of weighing the pros and cons, but Fenton, acting as the go-between, helped to set Lolich’s mind at ease. Finally, just a few minutes before ten o’clock, the lefty gave his ok.

“The deal was dead,” Fenton said soon afterward, “and I don’t mind saying I put it back together. Both clubs had struck out. I asked for a few concessions, and we finally were able to work it out. I realize this was a very traumatic decision for Mickey. It’s a tremendous emotional adjustment to think that after all these years he’ll be playing in a different uniform in a strange city.” Not to mention a different league. “And he was hurt to think that the Tigers would trade him after all he’s done.”

In the end, Lolich could not pass up the financial inducement. As Fenton put it, “The deal that was worked out will financially be sensational for Mickey and his wife Joyce and their three girls.”

Fenton was correct. The Mets would pay The Mick $125,000 in 1976, which, according to the website baseballreference.com, was the most he ever earned in a single season of playing ball. His highest annual income with the Tigers was $100,000 in both 1973 and ’74. After a 21-loss season, his salary was cut to $95,000 in ’75.

For Campbell, there was no looking back. In announcing the trade, he tried to strike a balance between honoring the past and paving the way toward a better future. “We had given up (on the deal). Then it was revived. Mickey Lolich has done a fine job for us. It was tough to give up a player of his stature. But we felt we had to do it for the overall good of the ball club.” Speaking of Staub, he remarked, “We got ourselves one helluva sound ballplayer.”

Campbell was asked if he had personally called Lolich after hearing of the veto. He had. “I told him we’re going through a rebuilding program and my first responsibility was to the ball club. There comes a time when a guy has to move on.”

It was actually a four-player deal. In addition to Lolich, the Tigers sent the Mets a 27-year-old outfielder named Billy Baldwin. As a rookie in ’75, he batted only .221 in 30 games with Detroit. New York, meanwhile, was also shipping Bill Laxton, 27, a left-handed reliever with a record of 0-3 and a 5.33 ERA in three seasons with the Phillies and Padres.

Lolich was 35 years old. By the baseball-card statistics of his day, he was coming off two sub-par seasons in which he’d gone 28-39 with a 3.99 ERA. Maybe he was no longer an ace, but he was clearly the Tigers best pitcher in 1975, the dean of a staff that featured two-time 20-game-winner Joe Coleman and youngsters Vern Ruhle, Lerrin LaGrow, and Ray Bare.

Some modern sabermetrics also indicate that Lolich was in decline in 1975. He struck out only 5.2 batters per nine innings, his fewest ever, and his WHIP was 1.346, his highest since 1970. He surrendered 9.7 hits per nine innings, a career high to that point. Nevertheless, his WAR of 4.2 was the fourth-best among starting pitchers in the American League East (only Jim Palmer, Catfish Hunter, and Dennis Eckersley had a higher figure).

At the time of the trade, Lolich had 207 victories, good for third on the club’s all-time list. He was already the greatest left-handed strikeout artist in history, and only five right-handers had more K’s than the portly Lolich.

Campbell cannot be entirely faulted for trading The Mick when he did. Sentiment aside, Lolich was not the pitcher he once was, and the team had been awful in 1975, with 102 losses. In addition, Campbell was right when he said that the team desperately needed a left-handed bat with some pop. Designated hitter Willie Horton led the Tigers with 92 RBIs that season. After that, it was a big drop-off to third baseman Aurelio Rodriguez’s total of 60.

In Staub, Detroit was getting a five-time All-Star who could rake with the best of them. He was also durable. Not your prototypical power hitter, he choked up high on the bat, which meant he usually made contact. He drove in 105 runs with the Mets in 1974, and hit .423 with a home run in the ’73 World Series.

Born in New Orleans, he was intelligent and articulate. A sophisticated bon vivant, they adored him in New York, where he also owned a couple of popular restaurants in Manhattan. He was a gourmet cook, and had once prepared eggplant seafood casserole for celebrity Barbara Walters on television. When he played in Montreal, he was known as “Le Grande Orange,” and endeared himself to Expos fans by learning to speak French and touring Canada to promote the team.

On the flip side, Staub resembled a statue on the basepaths and was a defensive liability. And at age 32, he wasn’t getting any younger. From 1967 to 1971, he had WARs of 5.1, 3.2, 6.2, 6.3, and 5.9. Since then, he was never higher than 2.9.

In 1976, Staub was the everyday right fielder for the Tigers, although he also played 36 games as the designated hitter. He made the All-Star team that year, played in every game, and finished with a .299 batting average, while knocking in 96. But by the next summer, Horton, another aging remnant of the ’68 championship team, was unceremoniously given a bus ticket out of town, and Staub took over his full-time DH role.

Staub was a veteran force on those young Tigers, also shepherding big league newcomers like Steve Kemp, Jason Thompson, and the infield twins, Alan Trammell and Lou Whitaker, into the clubhouse. He drove in over 100 runs in both ’77 and ’78, but he got off to a horrible start in 1979. He fell out of favor with many fans, who felt he wasn’t earning his paycheck. Staub, after all, was making $200,000, at the time the highest salary in franchise history. Additionally, he’d gone through a bitter two-month long contract dispute in the spring that played itself out on Detroit’s sports pages, and was a holdout until May 1. As his summer-long slump continued, the boo-birds at Tiger Stadium became quite vocal near the end.

Finally, on July 20, the Tigers dealt Staub, along with his .236 batting average, to Montreal, his old haunt. “It’s been a great three years in Detroit,” Staub insisted as he cleaned out his locker. In return, the club received cash (about $50,000) and a player to be named later (That would be catcher Randall Schafer, who never played a game in the big leagues and was out of baseball by 1980.).

Given Staub’s three-plus years of solid production, the Tigers probably got the better end of the deal. The Mets didn’t get much from Lolich, who had trouble adjusting to the National League and new pitching coahes who tried to change his methods. In 30 starts, he went 8-13 despite a solid 3.22 ERA.

After the season, Lolich retired to open his doughnut shop in Michigan. While he came back for a couple of seasons with San Diego, he was by that point just a middling relief pitcher in Padre brown and yellow. Perhaps all those innings had taken their toll; after peaking in his early 30s, Lolich was never again a dominant pitcher.

As for the other players in the Lolich-Staub deal, Laxton went 0-5 in his only season as a Tiger before being lost in the expansion draft. Baldwin played in nine games for the Mets before disappearing back into the minor leagues.

On a personal note, I was too young to see Lolich pitch, but Staub was one of my favorite Tigers growing up. I loved the way he carefully choked up on the bat, precisely one fist-length, before each at-bat. I didn’t pay much attention to his salary dispute back then. All I remember was I was happy to see him back in uniform after it was all over.

I remember not liking it when Tiger fans booed him in 1979. That was the first time I’d ever heard fans booing someone on the home team. My family was on vacation up north the day Staub was traded. I can still remember buying the Detroit Free Press the morning after and seeing the front-page headline: “Tigers Sell Staub to Montreal.” It was the first I heard about it. It didn’t exactly make my vacation.

But getting back to the trade, was it advantage Tigers? Or advantage Mets? What do you think?