Sam Crawford left the Detroit Tigers in 1917 but he went on to play four more years in California rather than stay in the major leagues to get 3,000 hits.

Sam Crawford liked baseball well enough, he started playing it (and other bat-and-ball games) when he was barely tall enough to reach the table in Nebraska in the 1880s. But he was also no fool, and after he established himself as one of the best batsmen in the professional game, he expected to be paid well for it.

Money — that’s why Sam joined the Detroit Tigers in 1902 and that’s why he left them 15 years later, and no personal glory or milestones would distract him from earning the salary he felt he deserved.

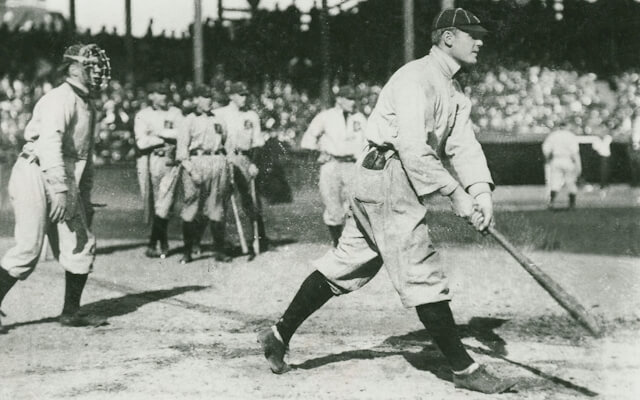

A tall lad, Crawford was unusually muscular for his era, which helped him stand out among his contemporaries. He used that heft to swat the baseball all over ballparks as he advanced through the minor leagues in the late 19th century. Crawford played in Ontario, Canada and then Columbus, Ohio before turning heads with his play in Grand Rapids. With the team that was appropriately called the “Furnituremakers,” Crawford reportedly once hit three homers in a game, most remarkably all three of them going over the fence. In an era when most homers were of the inside-the-park variety, it was notable. In 1899 he was snatched up by the Cincinnati Reds of the National League and he quickly gave notice that he was a man with great punch in his bat. He clubbed seven triples in only 31 games as a 19-year old and two years later he led the senior circuit with 16 home runs.

But while he was earning respect from his teammates and elsewhere in the league as a fine hitter, Sam was not getting respect from Cincinnati’s owner, a sourpuss named John T. Brush who was so miserly that he dreamed up the idea of a salary cap in the 19th century. In 1902, when the NL was feeling all sorts of pressure from the upstart new American League, Crawford pounced at the opportunity to jump to the AL for more money. Many stars did the same thing at that time, but it was a bold move because no one was sure what might happen in the “junior circuit.”

The move proved wise of course, as Crawford became the Tigers best player immediately. In his first year with Detroit, “Wahoo Sam” led the league in triples, something he would do four more times as he amassed a record 309 three-baggers in his career, many of them soaring over the heads of enemy outfielders at the corner of Michigan and Trumbull in Detroit’s Corktown.

With Ty Cobb often hitting in front of him, Crawford led the AL in runs batted in three times, including in 1915 when he was 35 years old, pretty old for a ballplayer in that era.

With Sam still poking the ball pretty well in his mid-thirties, it was puzzling when manager Hughie Jennings decided it was time to give more playing time to a young outfielder from San Francisco named Harry Heilmann. But that decision wasn’t being made solely by Jennings. Team owner Frank Navin was bristling a bit under the rising costs of fielding a big league baseball team. At that time Cobb was the biggest star in the game and the highest paid. In 1917 he was making $27,500, the equivalent of more than half a million today. That figure hampered Navin who was stingy in the contracts with his other players.

In the years when Ty Cobb was setting records for the Tigers, Crawford was the team’s next biggest star but he was not paid like it and that bothered him greatly. He took it for far longer than he cared to, and by 1917 when Heilmann was inserted into the starting lineup in his place when he had an off season, Wahoo Sam was fed up. That winter when Navin sent a contract that called for a big paycut to Sam at his home in Los Angeles, Crawford didn’t sign it. Instead he wrote the Detroit owner back and told him he was going to stay on the west coast.

In the long history of major league baseball only 29 players have reached 3,000 hits. Many batters have been unable to resist the magical 3,000-hit mark. Look no further than Ichiro Suzuki, signed to play another season in 2016 with the Marlins so he could he doggedly continue his pursuit of his 3,000th hit on this side of the Pacific Ocean.

But Sam Crawford never worried about 3,000 hits when he decided to leave the Tigers and stay home in California. He wanted respect and the way to spell R-E-S-P-E-C-T to Sam was in dollar bills. Instead of returning to the Tigers to get the 31 additional hits he needed to reach 3,000 (which most people hardly paid attention to anyway), he signed to play with the Los Angeles Angels. Major League Baseball was four decades away from expanding to California, but for Crawford the Pacific Coast League was big-time enough for him in 1918 when he signed a contract that called for him to make $3,500 more than Navin had paid him with the Tigers the previous season.

Sam showed that he wasn’t done as a player either. In 1918 he hit .292 but he was just warming up. In 1919 at age 39 he hit .360 with 239 hits, 41 doubles, 18 triples, and 14 home runs in the extended PCL schedule of 190 games. As a 40-year old he had 239 hits again and batted .332 with 21 of his patented triples. He was still clubbing triples and banging out hits at the age of 41 when he had 44 doubles and hit over .300 for LA in 1921. By that time he was making more than $20,000 playing in a “minor league” but he sure didn’t care.

Reportedly, Sam never cared that he fell 31 hits shy of 3,000 hits. In 1957, thanks in part to a lobbying campaign led by Cobb, Crawford was elected to the Hall of Fame, an honor that was overdue and well deserved. He didn’t get paid to go to Cooperstown, but Sam did go to the Hall of Fame that year and nearly every year after that until his death in 1968, a proud baseball legend even though he never got to the 3,000-hit milestone.