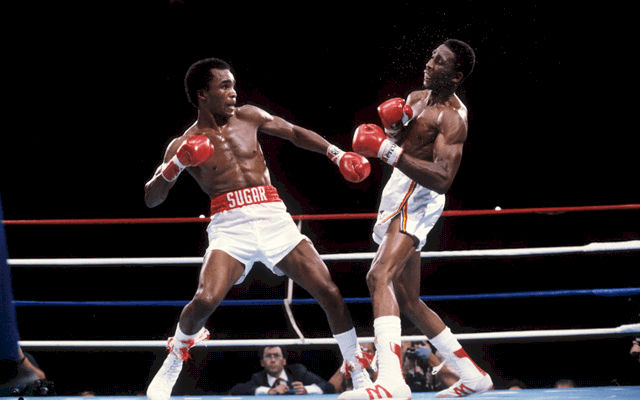

Sugar Ray Leonard and Tommy Hearns during their first fight, on September 16, 1981 in Las Vegas.

He never liked being called “The Hit Man,” and after going nearly 14 rounds with nemesis Sugar Ray Leonard under the bright lights at Caesar’s Palace in Las Vegas, Tommy Hearns didn’t feel like the “Motor City Cobra” (his preferred nickname) either.

Billed as “The Showdown,” the fight between Hearns and Leonard on September 16, 1981, was emblematic of how popular boxing was at that time, an era when fans of the sport loved watching the “little guys” more than the heavyweights.

Muhammad Ali revived the sport of boxing in the 1960s (then known as Cassius Clay) with his brash personality and flare, traits he borrowed from professional wrestling, which young Clay loved as a kid growing up in Memphis. Soon, nearly every fighter worth his weight in prize money was copying Ali’s schtick, but not as well. The heavyweight class was star-studded and minted in gold in the 1970s: Ali, Joe Frazier, George Foreman, Ken Norton, Leon Spinks, and others made the fight game legit again, at least in the eyes of many. Boxing was televised nationwide on Saturday afternoons, following a lead-in by cartoons. Boxing matches were events that attracted the biggest stars in media, Hollywood, finance, and politics. But then, just as Ali aged and started to slur his words, and the droll, unsexy Larry Holmes took the title, the heavyweight class fell out of favor. But fans and the media still loved boxing and a vacuum was created.

Along to fill that vacuum came 140-165 pound palookas who packed a punch, like Wilfredo Benitez, Roberto Duran, and the Olympic champion from 1976 in the light welterweight division, Ray Leonard, known as “Sugar.” How popular were these fighting “little guys?” Leonard attracted the services of trainer Angelo Dundee, the best in the business and former Ali camp member.

Nine months after Leonard turned professional, Detroit’s own Thomas Hearns joined him in the pro ranks. Hearns had been too young to fight for the United States in the ’76 Olympic Games. Instead, he fought in the amateur ranks out of the Kronk Gym located just off Chicago Avenue in western Detroit.

Hearns fought a lot. By the time he stepped into the ring for his first pro fight, the day after Thanksgiving in 1977, Tommy had fought 163 amateur bouts, winning 155 times. Facing some guy named Jerome Hill at historic Olympia Stadium in downtown Detroit, the site of many great moments by Gordie Howe and where Joe Louis successfully defended his title in 1941, Hearns recorded a knockout in the second round. Hill went down with a thud.

The lower ranks hadn’t seen the likes of Tommy Hearns in many years, if ever. In contrast to Leonard, who used lightning-quick speed and magical footwork to outpoint his opponents, Hearns socked his counterparts into submission with his strong right jabs and cement-like left-handed follow. He recorded a KO or TKO in each of his first 17 professional fights. Hearns was tall (just over 6 foot one inches) and he had long legs and long arms with an extraordinary 80-inch reach. He had a slim waist and rippling muscles on his shoulders, which gave him a “V” shape above his trunks. He wore his hair in a thick, curly afro, and his eyes were steely and focused. His nose flared and his neck was long, seeming to keep his head from punishment.

The Detroit boxer earned the USBA welterweight title after he defeated Angel Espada at Joe Louis Arena in marhc of 1980. Espada went to his knees 47 seconds into the fourth round and was counted out. exactly five months later, after fighting two warmup fights, Hearns won the WBA welterweight crown, vanquishing Jose Cuevas in the second round at The Joe. By then he had shunned the nickname “Hit Man” because of it’s negative connotations, but it was appropriate. Rebranded as the “Motor City Cobra,” he defended his title three times in 1980-81 and improved his sterling record to 32-0. He was one of the most popular athletes in the country. His face was on the cover of not just boxing magazines, but sporting weeklies and national magazines. Detroit loved him.

But Sugar Ray Leonard was always more popular. Lithe, quick, and with a devastating smile, Leonard was prettier. He was a mini-Ali. The paths of these two fighters — Hearns and Leonard — were bound to intersect.

The fight was billed as “The Showdown” and almost everyone picked Hearns to come out on top. He had hardly been challenged, recording 28 knockouts or TKOs, and he’d floored 21 of his opponents by the third round. Many experts thought that Hearns advantage in reach and his southpaw style would frustrate Sugar Ray. Surely if Leonard was forced to creep close to Hearns he’d be punished for it with several thwacks across the cranium.

Hearns prepared in northern Michigan (ironically at Sugar Loaf Resort in Leelanau County) and Emanuel Steward, the famed Detroit trainer, got his 22-year old fighter in fantastic shape. Contrary to his usual form, Leonard kept a low profile while training for the bout, which would be for the WBA welterwight belt.

Nearly 24,000 fans were at Caesar’s Palace to see the fight the evening of September 16th. Three hundred million watched on television. The fight was scheduled for 15 rounds. As expected, Leonard started the fight cautiously, dancing well out of reach of Hearns, who stalked him but showed patience. By the fifth round however, Hearns was doing damage with his jab and Sugar Ray developed a puffy bruise under one eye. Due to his aggressiveness, Hearns was well ahead on the scorecards as the fight entered the middle rounds.

Leonard countered with his best two rounds in six and seven, Hearns retreating to the ropes at one point. Later, experts would debate whether Leonard should have received 10-8 advantages for the two rounds, rather than 10-9.

The next few rounds saw a role reversal: Hearns started to box and Leonard tried to slug it out, knowing he needed to gain points. The southpaw from Detroit, looking poised against his older opponent, won three out of four rounds and was looking like he couldn’t be beat. Dundee told Leonard in the corner, “You’re blowing it, son!”

In spite of a rapidly swollen eye, Leonard came out in the 13th round and attacked Hearns, who tryed to dance his way out of harm. Never a graceful presence in the ring, Hearns bounced more than he danced, occasionally looking awkward and tenuous. In round #13, Leonard landed a combination and sent the taller Heanrs through the ropes, prompting a short count by the referee. Later in the same round, Hearns was knocked (or slipped) to the floor and received another short count. But he survived and needed to make it through only two more rounds to beat Leonard.

In the fourteenth, Leonard was like a man possessed, throwing caution to the wind and hurtling himself toward a tired Hearns. Sugar Ray landed two big combinations and Hearns covered up on the ropes, hanging on. Several punches later, most of which did not land, referee Davey Pearl waved both his arms above his head repeatedly at 1:45 of round #14, signalling the end of the fight. It was a technical knockout for Sugar Ray Leonard. Hearns looked baffled by the decision, but exhausted, he slunk to his corner, enveloped by his training team.

Scorecards showed that all three judges had Hearns leading: 124-122, 125-121, and 125-121. Leonard needed a knockout and he got it, technically at least. Predictably, there was controversy over the TKO, some experts believing that Hearns was not hurt that bad when the fight was stopped. Others wondered why the obvious swelling under Leonard’s left eye hadn’t precipitated a stoppage. Still others debated why Hearns was ahead that much to begin with on the scorecards.

The loss devastated Hearns. “It’s gotten to me,” he admitted a few years later. Indeed, over the three years after the loss to Sugar Ray, Hearns fought just six times. He won them all, but he wasn’t the same fighter he’d once been. he couldn’t shake that loss to Sugar Ray, he couldn’t stop thinking about how close he’d come to beating Leonard. He didn’t like how his image had changed.

“I am very aware of how the boxing world views me,” Hearns said, ” and it’s important to me to regain my reputation.”

In June of 1984, Hearns got the opportunity to redeem himself by facing Roberto Duran, the third actor in the great play that was lower weight boxing in the 1980s. At 1:05 of the second round, Hearns dropped Duran with a sweeping left hand and Duran stayed down. It was a knockout win at (of all places) Caesar’s Palace.

For that fight against Duran, a turning point in Hearns’ career, the name “Hit Man” was sewn back on his robe. From there, Tommy fought (and lost) a famous brawl-like battle with Marvin Hagler, won titles in three more weight classes, and earned a decision over Leonard in 1988 in their rematch.