Rusty Staub played for the Detroit Tigers from 1976 to 1979, earning an All-Star nod in ’76.

I was eight years old in the summer of 1976 , the perfect age for a first season as a baseball fanatic. Sure, I’d been aware of the Detroit Tigers before then, but in ’76 I was starting to form a conscious attachment to the team. And that summer there were a few Tigers who made an impact, including a funny-looking redhead who seemed to get a hit every time one of his teammates was on base.

Growing up in southwest Michigan I was like most other eight-year olds: I was enamored with Mark “The Bird” Fidrych that summer. The Bird was magical, an enthusiastic young pitcher with a mop-top full of curls and a knee-high fastball. I’d not seen many pitchers at that point in my life, but even a green-eared punk like me knew that The Bird was a rare ballplayer. He pranced around the diamond, he was fidgety on the mound, he bounced off the rubber after the inning was over, he shook his teammates hands after they made a good play. He talked to himself. He talked to the baseball!

Center fielder Ron LeFlore was also a natural favorite of mine. He was athletic and fast. Damned fast. He seemed to steal second base every time he got on first. He swung hard, so hard that he sometimes nearly fell over. He ran down fly balls at Tiger Stadium like a gazelle. He was a Detroiter.

But the third player I fell in love with in my first true season as a baseball nut was very unusual. He didn’t seem like a ballplayer at all. But I couldn’t take my eyes off him when he came to the plate. And unlike Fidrych and LeFlore, he had a near Hall of Fame career in more than 20 years in the game.

1976 was Rusty Staub’s first season in a Tiger uniform. He’d been acquired in a trade for Mickey Lolich. I wasn’t old enough to know what a Mickey Lolich was. I didn’t know that The Mick had won three games in the World Series only eight years prior. I didn’t know that Mickey had nearly pitched the Tigers to the pennant in 1972, or that in 1971 he threw nearly 400 innings! He was practically a pitching machine. But by 1975-76 he was an old man to this eight year old, and he belonged to the previous generation. I didn’t know well enough to know that Lolich-for-Staub was an unpopular trade. That the Tigers had traded away one of their most popular players. To me, Lolich wasn’t the Hero of ’68, he was a lefty with a big gut. (Sorry, Mick).

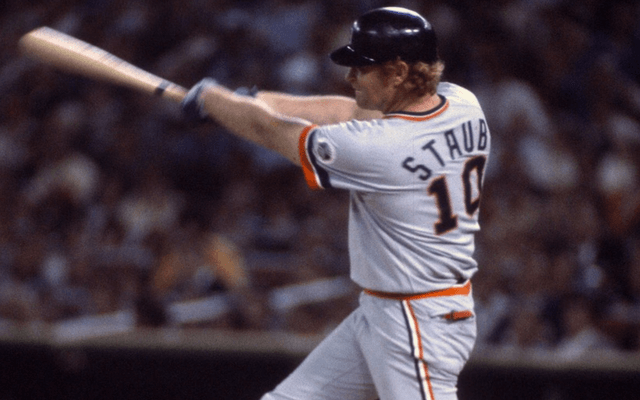

Without that prejudice, I wrapped my arms around Daniel Joseph Staub, the man they called Rusty. He was a goofy-looking athlete: Sort of top-heavy with pale skin, skinny arms, hands hidden in batting gloves that looked like he was teeing off on hole #1, knee-high striped socks, and that shocking red hair. And he didn’t act like a ballplayer.

When Ernie Harwell interviewed Staub as the “Florsheim Shoes Player of the Game,” Rusty’s voice was soft and a little high. His words were careful, he sounded more like a school principal than a ballplayer. When Rusty walked to the plate he moved gingerly and with little steps. (He was a notoriously slow runner). He gently squeezed the handle of the bat, flexing his fingers like he was tuning a flute rather than preparing a piece of lumber for battle with the pitcher. Staub was always dressed perfectly, his uniform precise, his pants just below his knees showing off the orange, white, and blue striped Tiger socks. It made his legs look skinny and fragile. His freckled arms didn’t look like they could possibly swing a bat hard enough to get the ball out of the infield.

But swing he could. Staub was what they called a “professional hitter.” His swing was level and fast. His kept his hands out in front of his chest, ready to spring the bat into the strike zone. He was a master of line drives. Once I saw him hit a home run to right field where the baseball looked like it never got more than 7-8 feet off the ground. He must have gotten about 50 hits a year where his line drive was 2-3 feet to the left side of the second baseman’s reach.

Rusty got a lot of those hits: more than 2,700 in his career. He got more than 500 with the Tigers in 3 1/2 seasons. He got more than 500 with Houston and the Expos and the Mets, as well. He was the only man to collect that many with four teams. No matter where Rusty went, his potent bat went with him. Professional hitter.

Later, when I was well past eight years old and working for the Baseball Hall of Fame, I met Rusty. He frequently made his way to Cooperstown to see his friend Jane Forbes Clark, the matriarch of that institution. Rusty liked to play golf, he liked to laugh, he liked to drink wine and eat good food. He loved people. He was polite to me when I interviewed him. I did a story on Rusty’s career, you can probably find it somewhere on the Internet, and he spent nearly an hour on the phone with me. We talked about everything: his being a star for the Colt 45s when he was 19; his love affair with the fans of Montreal; his World Series heroics with the Mets in 1973; his trade to the Tigers, the Summer of The Bird, his contract squabble with Detroit, and so on. He was interesting and generous with his time. He never had a bad word to say about anyone. It’s still one of my favorite assignments, because he was a great interview, but he was also one of my boyhood idols.

Rusty had been battling health problems the last few years. He wasn’t as visible in baseball as he once had been. He’d long since sold or closed his restaurants in New York. I always kept an eye on what the old redhead was up to. His death is very sad for me. It makes me think back to when I was eight.

Baseball fans never forget their first favorite player. I could imitate Rusty’s stance. I wanted to wear batting gloves because of him. For a while I wished my hair was red. He was fun to watch. He was a great hitter. Few pitchers could sneak a fastball by “Le Grande Orange.”

Rest in Peace, Rusty. This fan will never forget.