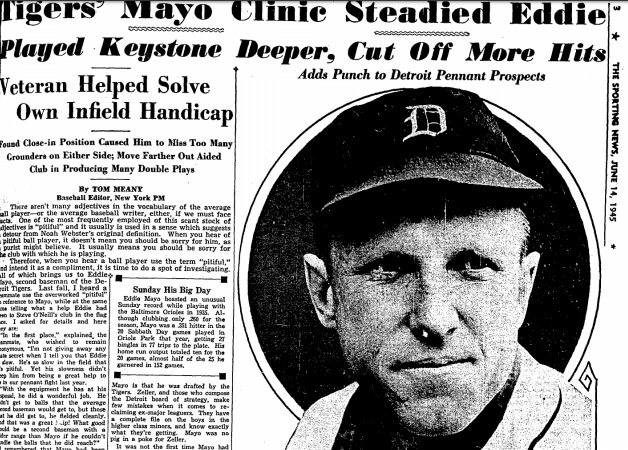

Eddie Mayo featured in the Sporting News in 1945.

A journeyman infielder when he came to Detroit in 1944, Eddie Mayo’s glove helped solidify the Tigers’ infield in the middle 1940s. Although his statistics were ordinary, the scrappy second baseman’s true value to the Tigers is best measured by results. During his first four seasons at Briggs Stadium, the Tigers won a World Series and finished second three times. In 1945, the Sporting News recognized Mayo’s contributions by naming him the American League’s Most Valuable Player and giving him a watch.

“We beat Chicago in the World Series that year,” Mayo once recalled. “I was aggressive and I played every day and I think I contributed to the team winning the championship. I contributed, I wasn’t responsible.

“We had a lot great players on that team—Hal Newhouser, Hank Greenberg, Rudy York, Dizzy Trout, Roy Cullenbine, Doc Cramer, Paul Richards. But I fought every pitch. I was a fighter. I had to work hard for everything I got.”

The son of a Polish immigrant who changed the family name from Mayoski, Mayo was born in Massachusetts in 1910. He grew up just a block away from a double-decked ballpark in Clifton, New Jersey, a baseball hotbed.

“You know, in those days before television, semipro baseball was a way of life,” Mayo said. “Every community had a team representing them, and they weren’t shy about importing players from wherever. In fact, I played for eight different teams in eight different cities. A different team each day and twice on Sunday. We’d play in Paterson, then hightail it up into New York state. It was quite common in north Jersey. You’d see the same fellas but on different teams.”

With exposure like that, it was only a matter of time before Mayo got noticed. One day in 1932, a scout named Ike McAuley came up to Mayo and said, “How’d you like to play for the Detroit Tigers?” Mayo signed a $175-a-month contract to play for the Class C team in Huntington, West Virginia.

This being the depth of the Great Depression, Mayo soon saw his salary trimmed to $100 per month, plus $1.50 a day in meal money. Even in 1932, that didn’t stretch far.

Mayo remembered the Beckley Hotel in Beckley, West Virginia, where the second floor featured one bathroom and a communal tub for 20 rooms. “They filled the tub up one time, that was it. At the end of the game, 15 muddy, clay-clogged kids jumped in and out of the tub and then went across the street to Greasy John’s, where you spent the balance of your dollar and a half a day on a hot dog and a coke.

“We had three Model A Fords at the time, with running boards on the side. They had an expansion luggage rack on the running board on the left side. You put your suit roll in there. After you’d played a night game you’d travel from Huntington, West Virginia, to Johnstown, Pennsylvania. That was about 350 or 400 miles. You’d drive all night long and get in Johnstown just in time to play another game. But that was baseball then. And you loved it. That was great.”

Mayo was a third baseman then. In 1936, he was sold to the Baltimore Orioles of the International League, who in turn traded him to the New York Giants. Mayo made a token appearance in that fall’s World Series between the Giants and the Yankees. The Giants traded Mayo to the Boston Braves, where he played parts of two seasons before being sold to Los Angeles, the Chicago Cubs’ farm team in the Pacific Coast League. He stayed there five years, waiting for a shot to break into the parent club’s lineup. Mayo had some great years in the PCL. “But there was no future with the Cubs because of Stan Hack at third and Billy Herman on second. They were fairly young, so I could’ve been with Los Angeles until I died of old age.”

Instead he was drafted by the Philadelphia A’s. It was 1943, and Mayo was 33 years old. The Sunday before the start of the regular season, Mayo was struck in the left eye by a thrown ball. The resulting retinal hemorrhage caused a small blind spot that never completely went away. Nonetheless, World War II was in full swing, and baseball was desperate for players. Mayo was a fine defender at third base for the A’s, but Philadelphia dropped him because of his .219 batting average, which was poor even by wartime standards.

That’s when he was picked up by the Tigers. Manager Steve O’Neill shifted the newcomer to second base. “In my opinion, he was the greatest humanist and manager of ballplayers that I’ve ever known,” Mayo said of O’Neill. “A great strategist and a very understanding man. He was the kind of manager who said, ‘You’re a major leaguer, you know how to play ball,’ and left you alone.”

O’Neill steered the club into two pennant races that weren’t settled until the final day of the season. In 1944, the Tigers were edged out by the St. Louis Browns. The following season, the Tigers outlasted three other teams. Mayo had his finest overall season in the bigs, batting .285 and hitting 10 home runs—both career highs—while flashing great defense at second base. In the seventh game of the World Series, he had two hits, scored twice, and drove in a pair of runs as the Tigers won, 7-2, behind Hal Newhouser’s complete-game performance.

“Hal was a great pitcher,” Mayo said. “He wasn’t a thrower…he was a pitcher. He had all the ammunition that goes with a great arm.”

Mayo played regular through 1948, after which he accepted an offer to manager the Tigers’ AAA club in Toledo. He went on to coach briefly with the Red Sox and Phillies before moving into private industry. He retired with a lifetime .252 average over nine major-league seasons.

Mayo had a couple of well-deserved nicknames: “Steady Eddie” and “Hotshot.” He was suspended for a year in the PCL for spitting on an umpire during a heated argument, a suspension that later was overruled. On another occasion, this time while with Detroit, he received a $25 fine from American League president Will Harridge “for knocking Skeeter Newsome on his ass.”

“He was a shortstop with Boston,” Mayo explained. “What happened? Well, were playing in Detroit and he hit one to left center. A three-base hit. One of the tricks of the trade when you’re a second baseman is to stand on the inside of the bag as the runner comes around. That way he has to make that wide turn. He can’t cut it short.

“So I’m just standing there, watching the outfield, and Newsome’s got to make that wide turn, which made his three-base hit a two-and-a-half-base hit. He sees he can’t make it to third. So, as he turned around and came back to second, he tossed out a couple expletives and popped me in the chest. I don’t know why he didn’t throw a haymaker, ‘cause he had me there, I wasn’t even looking for it. I threw off my glove and—I remember it like it was yesterday—three jabs and a hook and he was on his ass. He was one guy I really wanted to demolish.”

A successful business career enabled Mayo to enjoy a very comfortable lifestyle. He had homes in Berlin, Maryland, and Palm Springs, California, both on the golf course. He was 96 and the oldest living Tiger when he died in 2006. Long before then, however, he had quit watching the game he had once played with such passion, bemoaning the lack of fundamentals and discipline in the modern player. He grew irritated whenever someone pointed out to him some player who was hustling on the field.

“Well, Christ, 400 guys played like that back when there was 16 teams,” Mayo would respond. “Everybody dove into bases, everybody came in spikes high, everybody ran out a ground ball. If you didn’t play ball like that, you didn’t stick around.”