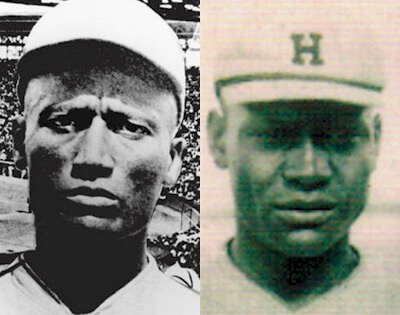

Turkey Stearnes and Edgar Wesley starred for the Detroit Stars of the Negro Leagues in the 1920s.

Baseball fans in these parts have seen some heavy-duty one-two punches in the batting order over the years, from Cabrera & Fielder all the way back to Cobb & Crawford. In-between there were such combos as Gibson & Parrish, Kaline & Cash, and Gehringer & Greenberg.

All those bashers suited up for the Tigers. However, for several years in the 1920s, an overlooked but equally devastating pair of sluggers created back-to-back trouble for Negro League pitchers at Mack Park: Norman “Turkey” Stearnes and Edgar Wesley.

Stearnes and Wesley were headliners on the Detroit Stars, a charter member of the Negro National League, the country’s top black circuit. Stearnes patrolled center field and typically batted third while Wesley, a fine glove man, anchored first base and usually hit clean-up. Both men batted and threw left. Each stood 5-foot-11, though Wesley was huskier than Turkey. Stearnes was quiet and temperate while Wesley hid his orneriness behind a deadpanned expression. Their birthdays were just six days apart (May 2 for Wesley, May 8 for Stearnes), though Wesley was 10 years older than Turkey. And, of course, both could mash the ball.

Wesley, a native Texan and a former member of Rube Foster’s famous Chicago American Giants, had already been a star for years in Detroit when Stearnes, a product of Nashville, Tennessee, first put on a Stars uniform in 1923. In 1920, Wesley had led the Negro National League in home runs; in 1919 and 1921, he’d tied for second.

In 1923, their first summer together, Turkey had 17 homers and 85 RBIs (both third in the league) and batted .362. Wesley had an off year, though his 16 round-trippers placed him fourth in that category. However, Wesley made up for it in a postseason exhibition series between the Stars and St. Louis Browns at Mack Park. In the first game of a three-game set, he poled a pair of homers, including a walk-off shot in the ninth, to climax a thrilling comeback win. He continued to hit and field well as the black pros beat the white big leaguers twice, causing Judge Landis to ban any further exhibitions between intact major-league and Negro League teams. Henceforth, the embarrassed commissioner decreed, only “all-star” teams could play each other, thus diluting the embarrassment of a major-league club losing to its supposed inferiors.

Wesley left Detroit for the new Eastern Colored League and split the 1924 season between Harrisburg and Brooklyn. Meanwhile, that year Stearnes won his first of five straight home run titles in a Detroit uniform.

Wesley returned to Detroit in 1925. That summer, he and Stearnes turned Negro League pitching inside out. Turkey hit .364 while topping the circuit in home runs (19) and RBIs (60). Wesley hit a blistering .413 to win the batting crown while finishing runner-up to Stearnes in homers and ribbies. Wesley would have posted even greater numbers, but his season was cut short by a broken ankle. He played another season and a half with the Stars before being traded to Cleveland in 1927. From there he went on to play ball in Cuba and South America, just one more itinerant ballplayer past his prime and trying to make a living the only way he knew how.

Injuries plagued Wesley throughout his career, which is why his numbers over the long haul weren’t nearly as impressive as Turkey’s. He batted .311 in a dozen Negro League seasons, the last of which was with the Atlantic City Bacharach Giants in 1931. It was the depths of the Great Depression. Wesley was 40 years old and in desperate need of a paycheck.

Meanwhile, Stearnes added a sixth home-run title in 1931 while dividing time between Detroit and Kansas City. He also led in RBIs six times (1925-28 and 1930-31). He 1929, the Stars’ last season at Mack Park, he hit .402 to win the batting championship; that season he also finished runner-up in homers and RBIs.

All told, Stearnes batted a collective .344 over 20 Negro League seasons. His 176 career home runs are easily the most hit in Negro Leagues play. He died in 1979, never receiving the acclaim he was entitled to during his lifetime. Most people just knew him as the quiet fellow who punched the clock at the Rouge plant for years. However, the Ford retiree was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2001 (the same year as Sparky Anderson) and today has a plaque at Comerica Park.

Wesley quickly faded away. As is the case with so many other Negro Leaguers, not much is known of his life away from the diamond. He was 75 years old when he died in Detroit one July day in 1966. By then Mack Park, the scene of many of his and Stearnes’s greatest hits, had been torn down.

One reply on “Stearnes and Wesley: The Bash Brothers of Mack Park“

Comments are closed.