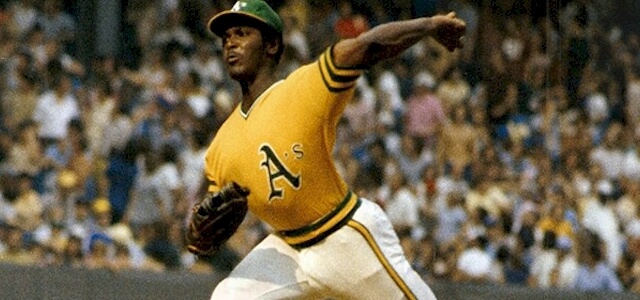

Lefty Vida Blue was available in 1976 to the highest bidder.

The 1976 Detroit Tigers weren’t very good. Their biggest star, of course, was Mark “The Bird” Fidrych. But the team tried to pull off a blockbuster deal that would have made them more intriguing (and more competitive) for the next several years.

Can you imagine (a healthy) Mark Fidrych and Vida Blue in the same rotation for Detroit?

The left-handed Blue was one of the big studs for Charlie Finley’s Oakland A’s dynasty. In his first full season in the big leagues in 1971, he won 24 games with an ERA of 1.82, while striking out 301 batters. He started the All-Star Game for the American League at Tiger Stadium, and won the Cy Young Award (beating out the Tigers’ own Mickey Lolich), as well as the A.L. MVP trophy. The A’s won five consecutive American League West titles from 1971-75, and World Series Championships in 1972, ’73, and ’74.

But now, in 1976, Finley was crying poverty. Unable to pay high salaries in the new free agency era, he was breaking up his great team piece by piece. He’d already lost Jim “Catfish” Hunter to free agency after the 1974 season, and traded away Reggie Jackson to Baltimore after ‘75. Vida Blue was still only 26 in 1976, and having a pretty good first half of the season, with a 6-6 record and an ERA hovering just over 3.00.

Finley was dangling Blue to any team that would listen.

The Tigers, and General Manager Jim Campbell, were listening.

The only problem was, so were George Steinbrenner’s New York Yankees.

Finley’s price tag for Blue was one million dollars, an astronomical figure at the time. Few teams would have been able to afford such an outlandish sum. The Yankees could, for sure, and maybe the Dodgers. It was a steep figure for Campbell and the Tigers. But a few days before the June 15 trading deadline, Campbell called up Finley to say that the Tigers were willing to meet his asking price.

Campbell insisted, however, that Finley hand over a 1977 contract, with Blue’s signature on it. The reason for this was obvious: Campbell wanted some guarantee that Blue wouldn’t leave via free agency as soon as the season was over.

But Campbell was also leery of getting into a bidding war with the Yankees, who he felt for sure would see his offer, and raise it.

“I was somewhat ashamed to get involved in it in the first place,” Campbell said later in the season. “I never thought I’d do something like that, but I did.”

Campbell’s comments seem odd today. After all, why should a general manager feel “ashamed” at offering a ton of money to buy a player in his prime? But we need to remember that free agency was unfamiliar territory in 1976. The baseball establishment, as well as the press and the public, weren’t quite sure what to make of it. Ever since the beginnings of professional baseball, players had been bound by the reserve clause, keeping them perpetually shackled to their team for their entire careers (unless they were traded, sold, or released).

But the times were definitely changing. The courts had re-interpreted the reserve clause to the players’ advantage, and free agency was now possible. Still, to many people in the game, the idea of a baseball player selling himself to the highest bidder seemed a sordid state of affairs.

Very soon, Finley called Campbell back to say that he couldn’t deliver a signed contract. The deal was off. A few days later, Finley made the announcement that he had sold Blue to the Yankees, for $1.5 million (in addition to a signed contract).

Campbell wasn’t surprised at the turn of events. He figured Blue had simply told Finley he’d prefer to go somewhere other than Detroit. The Yankees, after all, were in first place in the American League East, and most figured they would steamroll their way to the pennant (which they did, before losing in the World Series to the vaunted Cincinnati Reds).

“For a real good ballplayer,” said Campbell, “the number one attraction would be going to a ball club that’s already a contender. You can’t fault the player for that. A good ballplayer would be a fool if he didn’t take advantage of a situation like that.”

He sensed also that Detroit was at a geographical disadvantage to cities like New York or L.A., where players have greater opportunities to make money through endorsements. “If the player doesn’t like you, or your location, or your place in the standings, you can’t make a deal. The player can pick his own spot.”

What a concept, Mr. Campbell. Welcome to the brave new world of free agency.

Campbell’s final words on the subject were the kicker: “To be honest with you, we really couldn’t afford the million dollars. But we figured we either had to get into the crap game or get out. I think the elimination of the reserve clause is going to ruin the competitive balance of baseball. Everyone said it wouldn’t happen, but here we are the first example. The players are calling the shots. And most of them would prefer to remain in the same few cities.”

The postscript took a unique turn. Baseball Commissioner Bowie Kuhn voided Blue’s sale to the Yankees, claiming he wasn’t sure it was in the “best interests of baseball.” Blue remained with the A’s the rest of ’76, winning 18 games.

His final year in Oakland was 1977, when he lost 19 for an awful A’s team that finished dead last. After that season, the A’s traded Blue to San Francisco, where he had several more good years.

Given the circumstances, there wasn’t ever any realistic chance that Blue would have wound up with the Tigers. But the story is an interesting example of how teams were still feeling their way through free agency’s early years.