The Detroit Tigers paid $75,000 for Al Simmons in December of 1935.

Every baseball offseason, teams try to make a big splash with free agent signings or player trades. The ultimate goal is a world championship, and general managers get paid a lot of money to put the best club on the field.

Throughout baseball history, there are countless examples of wintertime deals, or player signings, that have helped put teams over the top. But what of the trades that didn’t work out so well? Or the free agents that turned out to be busts? Or the acquisitions that in the end were a waste of money? The human factor is the big unknown in any deal.

It can be difficult to predict how a player will respond to a new team, in a new city, with new expectations.

One transaction that didn’t work out so well for the Tigers was one that was hailed as a great move when it was made. The general opinion was that Detroit had just bought itself another World Series title.

It was December, 1935. The Tigers were barely two months removed from their first-ever world championship. But they knew they could use an upgrade in the outfield. At the December meetings in Chicago, owner Walter O. Briggs and his manager, Mickey Cochrane, opened up their wallets. They paid a then-princely price of $75,000 to the Chicago White Sox for a player who one day would have a plaque in Cooperstown.

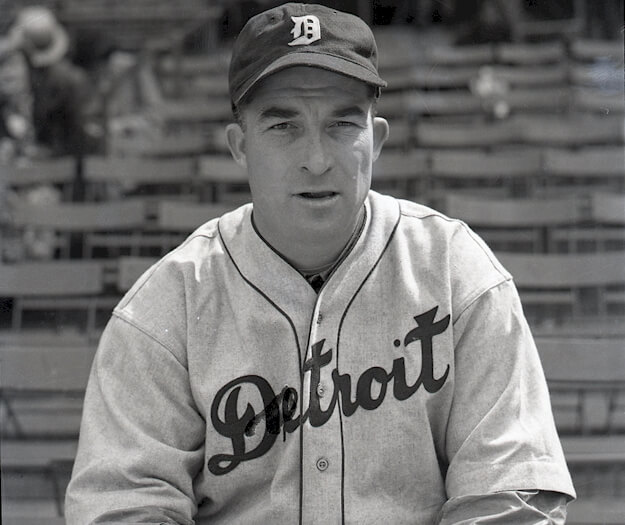

His name was Aloys Szymanski, also known by his Americanized name, Aloysius Harry Simmons. But everyone just called him Al. Or “Bucketfoot” Al.

For the Tigers, it looked like a wonderful acquisition. It’s true that Simmons was 33 years old, and coming off a sub-par year with the Sox in which he hit only .267 with 16 home runs and 79 RBIs. But he was one of the biggest superstars of his era, having gone to three World Series with the Philadelphia Athletics (winning two of them). Between 1924 and 1932, he’d averaged 23 home runs and 129 RBIs with Philly, while batting .358.

In September of ’32, the Sox purchased him for $100,000, along with two other players. Simmons’ first two seasons in the Windy City were very productive, but while his batting average remained high, his power numbers dipped.

Cochrane had a simple explanation as to why Simmons had struggled in 1935: “One trouble he had in Chicago was mental. Somehow, he got the notion in his head that he could not hit in the White Sox park. He won’t have any worry along that line here. He always liked to play at Navin Field.” Cochrane insisted Simmons was the best outfielder available, and that everyone he spoke to said the Tigers had greatly improved themselves.

When Simmons got word of the deal, he predicted he would hit .350 for Detroit. “I’ll show those fellows I’m not through.”

Said Charlie Gehringer, the Tigers’ future Hall of Fame second baseman: “With Al Simmons in our lineup, I don’t see how we could miss repeating.” Schoolboy Rowe, Detroit’s young star pitcher, agreed: “You can watch out for Al this summer. He’s going to have one of his best seasons.” Surrounded by Detroit’s other sluggers like Hank Greenberg and Goose Goslin, Simmons seemed poised to make a great comeback. And, most importantly, he was excited about playing for the Tigers.

But he got off to a slow start, and by the end of May he was hitting only .269 with four home runs. Making matters worse, the Tigers were sputtering along in fourth place, barely over .500. Simmons felt pressure to live up to the high expectations of others. He began hearing boos at Navin Field.

He eventually caught fire, hitting .394 in June, and .403 in August, turning the jeers to cheers. But it was a lost season for the Tigers, primarily because of injuries. Greenberg reinjured his wrist (he had originally hurt it sliding into home during the ’35 World Series) and played only twelve games all year. As for Cochrane, he suffered a nervous breakdown in early June and only played five games after that. The Tigers offense simply couldn’t make up such devastating losses. Detroit wound up in second place in 1936, a distant 19½ games behind the Yankees and their dynamite rookie Joe DiMaggio.

Simmons showed he was still a force to be reckoned with, batting .327 with 13 home runs, 38 doubles, 96 runs scored, and 112 RBIs. But while never a gazelle in the outfield, he had slowed down considerably, and the Tigers were concerned that he had put on a lot of weight during the season. Simmons, always a testy sort, didn’t fit in well in the clubhouse, and could be a difficult player to manage. Word soon got out that the Tigers would listen to offers for him.

None came, at least to the liking of Briggs, and when spring training rolled around, Simmons was still in a Detroit uniform. He had lost a few pounds, but looked even slower in the outfield than he had in 1936. In Goose Goslin and Simmons, Detroit had two foot-weary fly chasers in their mid-30’s. Looking to get younger, the team couldn’t keep both of them. Finally, a few weeks before the season opener, the Tigers sold Simmons to the Washington Senators for $15,000. It wasn’t exactly the return on his investment that Briggs had been looking for.

By that time, Simmons’ best years were behind him. He never again played more than 125 games in a season, or drove in 100 runs. He had been a great player for many years, but he was in the wrong place at the wrong time in his lone summer with the Tigers.