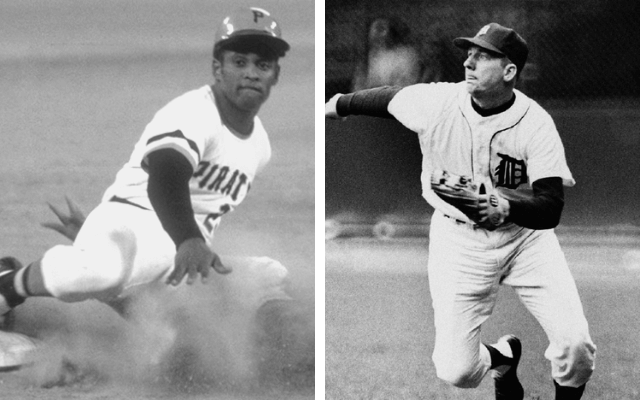

Roberto Clemente and Al Kaline were born four months apart in 1934, the former in Puerto Rico and the latter in Baltimore. Both became star right fielders for teams in the midwest starting in the mid-1950s. Each had a fantastic throwing arm and were playing in All-Star Games when they were barely old enough to shave. Kaline won a batting title first, in fact he was the youngest man to ever do so. But Clemente won four of them.

Both players were notoriously fragile: Kaline because he was born with a deformed foot and Clemente because he was a hypochondriac. Kaline exacerbated his physical handicap by also running into a lot of outfield walls, while Clemente stayed in the lineup a little more despite his frequent complaining about “not feeling right.”

Even though they were stars, both Clemente and Kaline had problems with hometown fans. In the early 1960s, Kaline quarreled with the front office over money and ticked off teammates when he grumbled about moving from right to center. He was often described as stoic or prickly. Clemente came to the National League when Latin ballplayers were still a novelty. He was frequently misquoted or made to look like a stereotypical Latino. As a result of mixed press, he withdrew.

Both Al Kaline and Roberto Clemente experienced a reputation boost late in their careers. Kaline finally played in a World Series in 1968 and exerted his leadership, while also making himself more available to the media. Clemente assumed a leadership with the Pirates later in his career when the team stocked the roster with many black and Latin-born players. His reputation for humanitarianism was legendary.

Each man, Clemente and Kaline, won a load of Gold Gloves, played in the All-Star Game every year, and earned lots of MVP votes. Clemente won an MVP Award, while Kaline finished as runnerup twice. Both men joined the 3,000-hit club and could fall out of bed in February and hit .300. Each man played their entire career for the same team in a hard-working, baseball-crazy city that didn’t get them a lot of attention nationally. Both were elected to the Hall of Fame the minute they were eligible, and both have statues outside the current ballparks in those cities.

Clemente was killed in a tragic plane crash, of course. Kaline went to work in the broadcast booth after retiring as a player and hasn’t missed a season since, still a Tiger in some capacity after all these years. Clemente’s legacy has been preserved by Major League Baseball through an award named after him that is presented to a player who exemplifies sportsmanship, good character and leadership on and off the field. Kaline was one of the first men to win that award.

The two players were not that different from each other in their results but they had markedly different styles at the plate. Clemente was a bad ball hitter who could tomahawk a high fastball into the seats, like he did at the 1971 All-Star Game in Detroit. Kaline had a brilliant swing that was efficient and steady. He rarely went into a slump for long. He was like a reliable watch. He’d get hurt for a few weeks almost every season, which kept him from getting 200 hits, 30 homers, and 100 RBIs. Kaline led the league in only five categories in his career: hits once, doubles once, batting once, and slugging and OPS once.

Clemente was flashier than Kaline. He would dive for balls in the outfield that his teammates were sure he could have gotten to on his feet. He threw the baseball back to the infield underhand, and he loved to show off his strong right arm by zipping the ball from the deep regions of the ballpark to third base or home even when it was unnecessary. At times in his career he would lose concentration in the outfield, turning his head to peer around the ballpark. He was a flash of energy and movement when he ran: his arms, legs, head, and chest seemed to be moving in opposite directions as he traversed the base paths. In contrast, Kaline glided across the diamond. If he wasn’t scaling a wall, Al was running in an scientifically-sound path to the ball and making the catch in text book fashion, as if guided by a dispatcher. He was a master at positioning his body so he could unleash a quick throw. In both cases, with Clemente and Kaline, runners basically stopped running on them.

With all their outward differences, Clemente and Kaline ended up remarkably close on the statistical side. Wins Above Replacement has Kaline at 92.5 for his career, Clemente at 94.5. According to OPS+, Kaline is slightly better, 134-130. Their raw career totals aren’t that far apart.

Here’s a comparison of the two based on per 162 game averages:

| H | R | 2B | 3B | HR | RBI | BB | TB | TRB | AVG | SLG | OBP | |

| Clemente | 200 | 94 | 29 | 11 | 16 | 87 | 41 | 299 | 243 | .317 | .475 | .359 |

| Kaline | 172 | 93 | 28 | 4 | 23 | 90 | 73 | 277 | 248 | .297 | .480 | .376 |

Clemente had 28 more hits per season than Kaline, but 27 of those were singles because Kaline was even in extra-base hits, while hitting seven more homers. Those 27 singles have value, but when you see that Kaline walked 23 more times and also had the edge in power, it pushes them so close that it’s hard to pick one over the other.

Both men are legends, and we know who Detroit fans like, but those fans in Pittsburgh who saw Clemente will back their man.