In a 15-year pro career, Pacella wore 18 different uniforms and pitched in 12 leagues, from Appalachia to Denver to Yokohama, Japan. He started, he relieved, he mopped up. He played on dusty fields and he played in The Show. He defeated a Hall of Famer, and he was beaten up by minor leaguers. He frequently frustrated his managers because of his wildness. But wherever he was and whichever uniform Pacella wore, he threw the baseball hard.

He just never really knew where it was going.

The Mets drafted Pacella out of high school in the 1974 draft, picking the Brooklyn kid in the fourth round. Pacella was a tall teenager with broad shoulders and long legs. His two most distinguishing features were his right shoulder and his thick mop of hair, which escaped from the confinement of his baseball cap like East Germans trying to crawl over the Berlin Wall. Pacella was a noted flamethrower in high school, and he even struck fear in opposing batters, according to his catcher.

“I caught Johnny at Connetquot High School on Long Island,” his high school teammate said. “He threw so hard that I needed an extra pad in my catcher’s glove, but my hand still looked like raw meat at the end of every game. Towards the end of the season, his reputation for throwing hard stuff got around the league and I remember seeing one kid’s knees shaking when he stood in the batter’s box. I laughed so hard I almost wet myself! I’m just glad John was on my team.”

The right-hander was only 17 when he began his career with the Mets’ rookie league team in Marion, Virginia. But he almost threw himself out of professional baseball before he could turn 18. Pacella lost seven of his first eight decisions and walked 32 batters in 43 innings. He had no idea what he was doing.

“I was close to being released,” Pacella told The Sporting News. “A couple of guys told me that I’d never make it, that I just didn’t know how to pitch.”

Pacella walked nearly seven batters per nine innings in Marion, but he persevered. Plus he had that knee-shaking fastball. Late in his fourth pro season, he received “the call” to go to the big leagues. When he arrived in New York for in September of 1977, he was met by Joe Torre, a fellow Brooklynite, and the Mets’ player-manager.

Torre encouraged Pacella to trust his stuff, and he found a lopsided game to debut his new fastball specialist. With New York trailing the Phillies 6-2, Pacella entered to pitch the seventh inning at Veterans Stadium. He got through his first inning without surrendering a run, but in the eighth, his wildness emerged. Pacella walked two batters, tossed an errant pickoff throw to first base, and allowed two runs. Welcome to the big leagues, kid.

It wasn’t long after Pacella was in New York that folks started to notice he lost his cap a lot. The pitcher didn’t actually misplace his cap, it flew off his head almost every time he threw a pitch.

“I don’t know when it started,” Pacella said. “I know it became a big deal, it was [what I] was known for more than anything else.”

Pacella had a thick head of hair and he usually wore his cap high on his head. But even when he pulled it tight around his noggin – it would fall off when he unleashed his fastball. It was so annoying that he took to tossing his warm-up pitches in the bullpen without a cap. The Mets had to hang a sheet in their bullpen to hide it, because league rules required players to wear a cap while in uniform on the field. It got so bad, that when Pacella entered games, fans at Shea Stadium would keep a “Cap Count”, tallying each time his blue Mets cap would fall to the dirt.

The Mets sent Pacella up and down and all around the map for a few years, dispatching him to farm clubs where they trusted a new pitching coach to teach the tall pitcher how to find home plate. He gradually lowered his walk rate, and in 1980 he made the team out of spring training. The Sporting News did a story on Pacella that focused on his newfound mental approach. Pacella claimed that he meditated before starts and that it might have helped him be more effective and throw more strikes. That type of talk was too “new age” for that era, and TSN wrote that Pacella “hypnotized” himself before pitching. But it was more like extra mental focus than any mental magic.

Torre was still the manager, and in June of 1980 he moved Pacella out of the pen and into his rotation. These were the years between the Seaver Era and the Gooden Era, and the Mets were desperate for pitching. In his first few starts, Pacella kept losing his cap, overthrowing, and walking about one batter per inning. But in late June he had what would turn out to be his best outing in the big leagues.

On Friday, June 27, 1980, the Mets were in Philly to face the Phils, the best team in the East and the eventual pennant-winners. Pacella was tabbed to start against Steve Carlton, the Phillies’ ace and future Hall of Famer. But that evening, Pacella had both velocity and accuracy, though initially it didn’t appear to be the case. He walked leadoff man Pete Rose, in what might have seemed like a “here we go again” moment. But the next batter bounced into a double play, and then Pacella struck out home run champion and eventual MVP Mike Schmidt with his fastball. Pacella struck out Schmidt twice that night, on his way to seven K’s and a 3-2 victory over Carlton and the Phillies. It was his first victory in the big leagues, but there would be only three more.

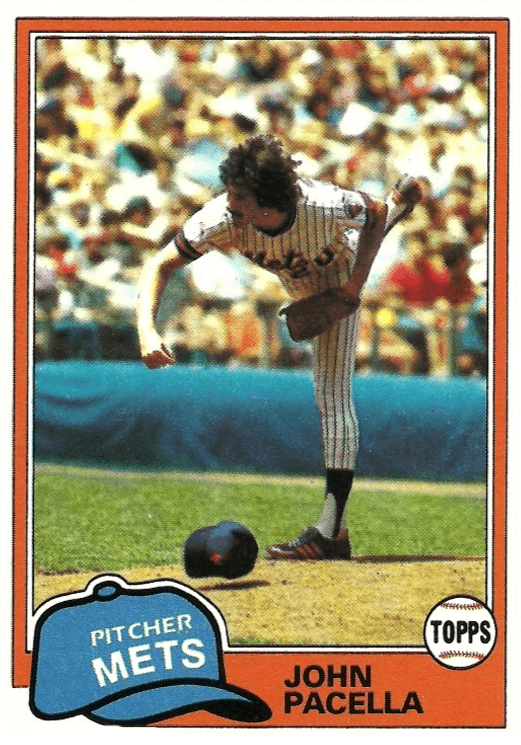

Control problems hampered Pacella, and at the 1980 MLB Winter Meetings the Mets dealt him to San Diego. He never wore the brown and mustard in San Diego however, because he was in turn traded to the Yankees a few months later, on the eve of the 1981 season. He spent the entire year in the minors, but Topps still issued a baseball card for him that year, and it became very popular. The card shows Pacella violently following through on a delivery at Shea Stadium, with his cap having fallen off his head and only inches from the ground. It’s one of then most iconic “in-action” photos to grace a card in that set, perfectly capturing the cult-status essence of an otherwise unknown ballplayer.

The Yankees brought Pacella north with the team in 1982, and the righty made two starts that season. He split the year between the Pinstripes and the Twins, mostly pitching out of the bullpen, and mostly throwing pitches out of the strike zone. He walked 46 batters in 61 2/3 innings and had a miserable 7.30 ERA. Over the next few years he was traded, from Minnesota to Texas, where he was released. He was nearing his late 20s, and while he could still throw a baseball 95 miles per hour, he was not really a pitcher as much as he was a thrower. The Orioles picked him up, and released him. The Tigers took a chance on him in 1986, as an option late in games when they needed a strikeout. But he walked seven batters in his third game for Sparky Anderson and was released a few weeks later. His brief stint with Detroit was the last time Pacella pitched in the big leagues.

For one season, Pacella took his arm to Japan, where his Japanese league cap fell to the mound dirt, but he still threw too many bases on balls. He came back to the U.S. and tried to make it back to the majors, but threw his last pitch for the Toledo Mud Hens in 1988. He was 31 years old.

After his playing career, Pacella settled in Ohio, where he still lives and works with young pitchers at a baseball school. No word on whether his cap stays on his head or not.

One reply on “Wild-throwing John Pacella earned notoriety for losing his cap“

Comments are closed.