The 1921 Detroit Tigers hit .316 as a team, establishing an American League record that still stands.

Since 1901, it has happened 40 times.

Surprisingly, we have not seen it in over 65 years.

Will it ever happen again?

I am talking about a major league baseball team hitting at least .300 in a season.

The Detroit Tigers have accomplished the feat six times, the most of any club.

The Boston Red Sox were the last to do it, when they batted a collective .302 in 1950.

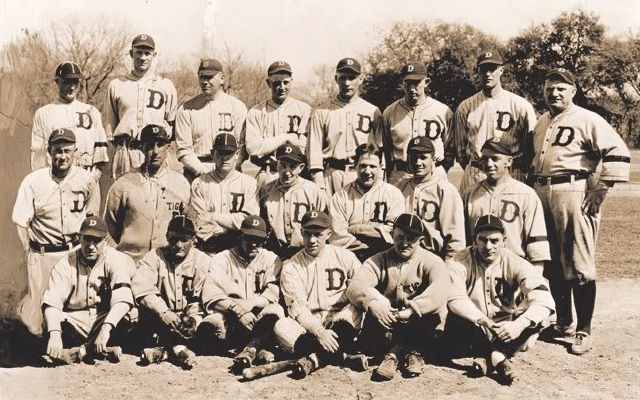

The Tigers first turned the trick in 1921. The game was undergoing a seismic change. It was the dawning of the age of Babe Ruth, who was swatting homers with great regularity in Upper Manhattan and across the land. The Deadball Era, meanwhile, was going the way of the horse and buggy.

Ty Cobb, however, was still roaming the outfield at Michigan and Trumbull. The 34-year-old hit .389 in ’21, which was not even good enough to lead the team. That honor belonged to fly chaser Harry Heilmann who finished at .394. Bobby Veach, at .338, rounded out Detroit’s dynamic outfield. The Tigers hit .316 that summer, establishing an all-time American League record that may never be broken. In 2016 only one individual Tiger hit that high—Miguel Cabrera—who hit .316 on the nose.

Baseball fans in the 1920’s saw plenty of offense, as home runs and batting averages were up across the board. Several teams hit .300 in a season. Detroit did it again in 1922, hitting .306. Cobb swatted the ball at a .401 clip, his third and final .400 season. In 1923, the Georgia Peach “slumped” to .340, but Heilmann picked up the slack, winning the batting title at .403, the only time in his career he would hit over .400. That Detroit squad hit an even .300, just below the Cleveland Indians, who batted .301 as a team, with Tris Speaker leading the way with a .380 mark.

The Tigers came close in 1924, winding up at .298. The following year, they batted .302. Once again, it was the outfield that shone brightest. Heilmann (.393) and Cobb (.378), were their usual stellar selves. The biggest surprise was a previously unknown 27-year-old left fielder named Absalom Holbrook Wingo, better known simply as “Red.” Wingo came out of nowhere to bat .370. It was one of the greatest fluke years in the history of the game. Wingo’s game was limited: he was atrocious with the glove, and lacked extra-base power. After playing only three more seasons in the majors, never hitting higher than .285, he disappeared into the minor leagues where he frequently hit over .300 against inferior competition.

After going without a pennant since 1909, the Tigers finally reached the American League summit in 1934, a year that also saw them hit an even .300 to top the circuit. That team featured a well-balanced attack, led by second baseman Charlie Gehringer at .356. First baseman Hank Greenberg (.339), catcher Mickey Cochrane (.320), third baseman Marv Owen (.317), and outfielders Jo-Jo White (.313), Goose Goslin (.305), and Gee Walker (.300) could also rake. Schoolboy Rowe was probably the best-hitting pitcher of his time. On September 9 that year, Rowe started a game in which all nine hitters in the Detroit lineup boasted at least a .300 average.

Detroit lost to the St. Louis Cardinals in the World Series that year, and while they did not bat .300 in 1935, they did win the world championship by beating the Chicago Cubs. In ’36, the Tigers hit exactly .300 once again, although they finished far behind the American League champion New York Yankees, who also batted .300 that year. The Yanks had a pretty fair rookie by the name of Joe DiMaggio, who only hit .323 with 29 home runs and 125 runs driven in. Neither Detroit nor New York, however, led the league in hitting. Indeed, it was the Cleveland Indians at .304, who finished at the top. Their weak pitching, however, contributed to only a fifth-place finish in the eight-team league.

In the ensuing decades, a few teams have come somewhat close to hitting the magic .300 mark over a season (notably the Indians of the late 1990’s), but it has proven to be elusive.