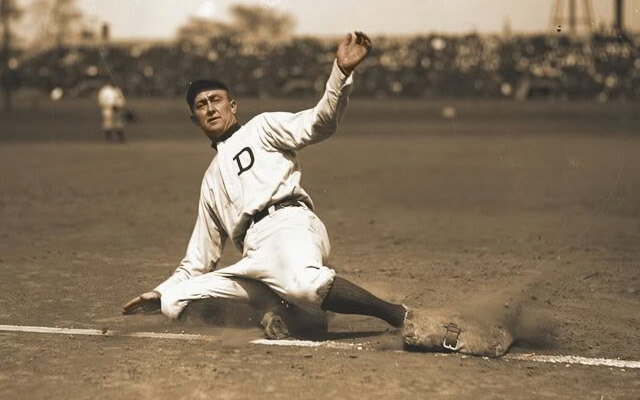

Ty Cobb tried to steal home 99 times in his career, including the one time he was successful in the World Series.

Context is important. Without it, you’ll get bamboozled.

In 1942, The Sporting News polled 102 former managers and players, asking them to choose the greatest player of all-time. The second place finisher was Honus Wagner with 17 votes. The mighty Babe Ruth got 11. The runaway winner was Ty Cobb, who got 60 votes, compared to 42 for the rest of the field. Many of the voters submitted comments, and here are a few of them:

“The greatest ballplayer to ever set foot on a diamond.”

“He had brains in his feet.”

“A fierce competitor and a team player.”

One voter, an unidentified former player who battled Cobb for years, said “Everyone in the league feared him, but we respected him.”

No one mentioned dirty play, nor did they say anything about Ty sharpening his spikes. That’s because Ty Cobb wasn’t a dirty player.

Let me rephrase that: Ty Cobb wasn’t the only dirty player.

Cobb once said, “When I began playing the game, baseball was about as gentlemanly as a kick in the crotch.” That about says it all. When Cobb stepped off a train and planted his foot on Michigan soil in 1905, the first time he had ever been north of the Mason-Dixon Line, baseball was a rugged game. Consider these facts about that era:

- In the early 1900s, common baserunning tactics included cutting across the field when the umpire wasn’t looking, grabbing a baserunner’s belt to hold him from advancing a base, and tripping and tackling runners. Catchers were known to toss their mask into the basepath or even grab a discarded bat to place in the path of a runner approaching home plate.

- Several times in the years before World War I, an umpire was punched by a player. As late as the 1940s, there are instances of players kicking umpires without anyone making a big deal out of it.

- No fewer than a dozen professional ballplayers between the years 1900 and 1920 hopped into the crowd to fight fans. The stands were frequently the scene of fights, brawls, and assaults.

- Infields were rocky, with ungroomed surfaces that caused pain and bruises to sliding runners.

- A single baseball was often used for an entire game, darkening until it was difficult to see. Batters were beaned, thrown at, and spiked as they ran to first base on bunt attempts. A favorite ploy of catchers was to throw the ball back to the pitcher dangerously close to hitting the batter in the head.

- Teammates rarely welcomed young players. Instead, the veterans brutally hazed rookies. A few of the common tactics were sawing a rookie’s bats in half, burning his clothes, and locking him out of his hotel room.

- Fans frequently tossed bottles, fruit, and rocks at players. Once, in Boston only a few years after Fenway Park opened, fans standing in roped off “overflow” sections spilled onto the field and surrounded Cobb after he caught the last out of the game, creating a dangerous scene where thousands of enemy fans were taunting an opposing player from only a few feet away.

Cobb was the best player in an era when baseball was played by tough men in low-scoring games where every base gained and every run scored was crucial. He might have spiked more players than anyone, but that’s because he was on base more than anyone else, stealing more bases than anyone ever had. Yes, he beat up a fan, but so did Rogers Hornsby and Babe Ruth. Cobb was, as The Sporting News once wrote, “truculent and quarrelsome.” But back then the game was like war. Ty didn’t go looking for a fight: there were opportunities for fisticuffs nearly every day.

Ty bristled at the accusations of his dirty play. “I never spiked a player if I could avoid it,” Cobb said. “If a player was in front of the bag, there was no way to avoid it. I always went in with one foot, trying to get my toe in. But if a fielder was standing in front, he might get it on his legs or arms.”

Shortstop Joe Sewell recalled a play in the early 1920s when a throw pulled him off the bag at second with Cobb coming from first. “He saw what had happened to me [and] that I was in no position to protect myself,” Sewell said. “The left leg he had out in front of him went down and he jammed it right into the leg on which he was sliding. He was cut right to the bone. They had to carry him off the field and stitch him up in the clubhouse.” Several players, including Ray Schalk, Red Faber, and Red Ormsby, defended Cobb against the accusations that he spiked fielders on purpose. “As long as I watched him play, nobody could convince me that Cobb went out of his way to hurt anybody,” Faber said.

In 1928 when he ended his career, and in 1936 when he received the most votes for election to the brand-spanking-new Baseball Hall of Fame, and in 1942, when his peers overwhelmingly rated him as the greatest player in history, Cobb wasn’t considered a dirty player. He was no scoundrel. He was a cranky man with few friends, but he was respected as the best all-around player in the history of the sport, a thinking man’s genius in spikes.

It was only late in his life after sportswriter Al Stump slandered Ty’s reputation in a series of articles, that Cobb became a monster. Unfortunately, for decades that narrative held sway, and in the 1990s, a dreadful movie (Cobb starring Tommy Lee Jones) solidified the myth of Ty Cobb as a cruel racist.

Stump was a thief and a liar, proven on both counts. Even after several books were published that show the real (and still imperfect) Cobb, many people still insist the Stump version is the real one. In his first Historical Baseball Abstract, Bill James pondered the theory that Cobb was a psychopath. Yes, really. An otherwise wonderful book was tarnished by James’ amateur psychoanalysis.

In his later years, when he grew plump at the waist, Cobb took it upon himself to keep the memory of his contemporaries alive. In a letter to J.G. Taylor Spink, editor of The Sporting News, Ty wrote: “These old boys are peculiar that way. When they are through with the game, they simply go back and hide away. They have lived a baseball life, in hotels, on trains, and they are tired. They get old, they realize their day has passed and they simply go away.”

Cobb was stubborn. He was hard-headed. He wouldn’t “simply go away.” He kept talking about the deadball era, his teammates, and the players he competed against. Most of them, if they were honest, swore to his greatness and his sportsmanship. But it was more interesting to listen to the people who told the fibs about Cobb. His legend became twisted, and he ended up more myth than man, an easy target for critics.