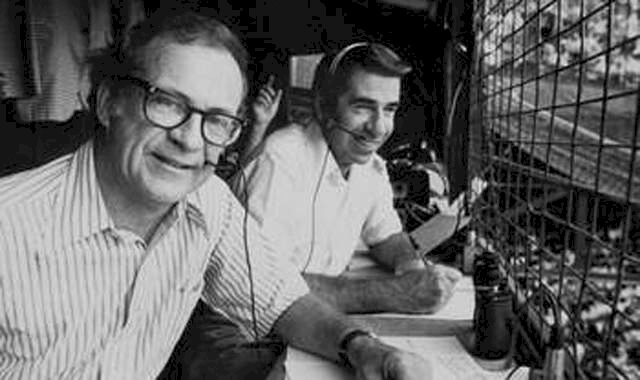

For many years the radio team of Ernie Harwell and Paul Carey filled the Michigan airwaves with brilliant baseball narration for the Detroit Tigers.

There are two kinds of baseball fans: The kind that likes listening to games on the radio. And the kind that doesn’t.

I think this may be mostly a generational thing. Younger fans today can’t really grasp the concept of how we used to “consume” sports way back in the dark ages.

Today, every game for every team is available to watch on TV, on your computer, or on your smartphone or tablet.

If we don’t want to sit through an entire game, we can just watch the highlights later on one of our many devices.

While baseball’s television ratings may be floundering, this is really a golden era for baseball viewing. The games can be consumed in so many different ways, and on so many platforms, that it boggles the mind.

When I started coming of age as a young baseball fan in the late 1970s and early ‘80s, it was an entirely different world.

The Detroit Tigers didn’t televise every game back then. In fact, it was always a special treat to settle in for a game with George Kell and Al Kaline. Those two were a perfect pair on TV.

Kell, in his Arkansas twang, would say that a pitch was “up high,” or “down low.” Sometimes a hitter “broke his bat half in two.” And sometimes a hitter would line one into the fans sitting behind the dugout, and Kell would shout “Look out!” As if they could hear him.

Kaline, on the other hand, was good for the occasional insight, but he sometimes stumbled through player names. Al Bumbry became Al Blumbly, while Tom Seaver became Tom Seavers. Rusty Kuntz became, well, I’ll leave that one to your imagination.

Unlike the mere handful of TV games, when I was a kid the Tigers broadcast every single game on the radio.

My summer evenings were spent listening to Ernie Harwell and Paul Carey. Detroiters were spoiled with those guys for a long, long time.

I’m not going to tell any Harwell stories, because you’ve probably heard them all.

But here’s a couple of tales that reveal just how old-school Carey was.

In the early 1980s, the Royals Stadium P.A. system was kind of cutting-edge when it came to bells and whistles. While other ballparks were still employing the traditional organ players, the Royals featured pre-recorded rock music and electronic sounds that you didn’t hear yet anywhere else. I can still recall Carey doing the play-by-play one night from Kansas City. The sound system was loudly cranking out what resembled the huffing and puffing of an annoying choo-choo train. Finally a flustered Carey, who you could tell was trying to be heard over the incessant cacophony, blurted out: “Well, I think we’ve had just about enough of that!”

Poor Carey. He would have cringed at the endless onslaught of noise in today’s baseball stadiums.

My other Paul Carey story, however, isn’t about anything he said during a game. One night just before the start of the 1988 season, he hosted a special round-table discussion on WJR in which listeners could call in (what a concept!) with questions about the Tigers’ chances, or just about baseball in general.

One listener called in and started to make the case that Nolan Ryan should have won the National League Cy Young Award in 1987 (He’d actually finished a distant fifth behind winner Steve Bedrosian). The caller laid out some convincing facts in Ryan’s defense: He’d led the National League in ERA at 2.76, and strikeouts with 270. Ryan, the caller said, had been the victim of non-support all season.

Today, I can look up Ryan’s record and learn that in 16 of his 34 starts in 1987, the Astros scored two or fewer runs, and that his record in those 16 games was 1-13 with a 3.03 ERA.

The caller, of course, didn’t have all this information at his fingertips, but he was on the right track. That I even remember this radio moment decades after the fact is perhaps explained by saying it was an epiphany for me as I listened. It was one of the first times I’d ever heard someone trying to look beyond just wins and losses, of delving deeper in an effort to quantify a pitcher’s total effectiveness. It was my personal awakening into the world of sabermetrics.

Carey, the staunch traditionalist, was having none of it. He quickly interrupted the caller. “And what was Ryan’s record last year?” he asked in that deep baritone voice.

“8-16,” the caller answered sheepishly.

“Well, that’s all you need to know,” Carey declared emphatically, and hung up.

Harwell and Carey were masters at their craft. Calling a baseball game on the radio takes skill and intelligence, along with perfect cadence and timing. A good radio announcer must have the ability to paint visual pictures on the fly, to inform, to entertain, and to convey the idea that they are describing something worth listening to, even in the midst a 10-0 blowout.

Baseball is the only sport that is actually better heard on radio than it is viewed on TV.

With cell phones and the internet, it’s a great time to be a fan of baseball on the radio. We can listen to any local or out-of-market games we want. We can sample every team’s announcers, comparing one to the other, like tasting different beers. And it is available everywhere, whenever we want it.

If Dan Dickerson starts to spend too many innings rambling on about some esoteric stat, or if Jim Price can’t decide if that last pitch was a two-seamer or a three-seamer, I’m only a few taps away from switching over to some other game.

Baseball and radio: It’s how Abner Doubleday would have wanted it.