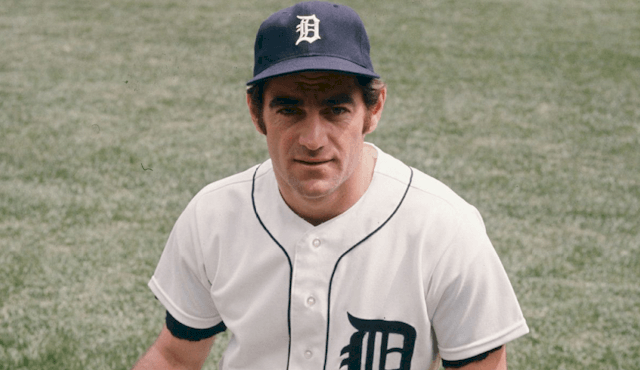

Infielder Dick McAuliffe played 14 seasons for the Detroit Tigers from 1960 to 1973.

He was a hero to a generation of Detroit Tiger fans, a tough competitor who took no prisoners on the diamond.

He was the star second baseman on a championship baseball team, and his grit and determination to succeed was equaled only by that of the proud city for which he played for 14 years.

The Tigers announced that Dick McAuliffe passed away last week at the age of 76. No cause of death was given.

Though not a big man, he had the heart of a champion.

Born in Hartford, Connecticut on November 29, 1939, he grew up in Unionville, a nearby suburb. McAuliffe played football, basketball, and baseball in high school.

Pitching in a state championship game, he was yanked early due to wildness, was moved over to third base, and made a couple of swell defensive plays. Sitting in the stands that afternoon was Tiger scout Lew Cassell, who was so impressed with the kid that he signed him to a contract two weeks later. With the ink on his high school diploma barely dry, and a $500 bonus in his back pocket, Richard John McAuliffe was now a professional baseball player.

But it wasn’t an easy first summer for the 17-year-old. With the Class D Erie Sailors, McAuliffe hit only .206 in 60 games. It was a slow, steady progression up the organizational ladder for the stocky 5’11,” 160-pound shortstop. After hitting .301 in Knoxville in 1960, he was promoted to Detroit, seeing his first big league action on September 17 at Briggs Stadium. Pinch-hitting in the ninth inning for pitcher Paul Foytack in a blowout loss, McAuliffe drew a base on balls.

It was an appropriate start for a man with a good eye at the plate who was expert at drawing walks. He got into eight games in that season’s final month, with seven hits in 27 at-bats.

Following a sizzling start in the thin air at Triple-A Denver in 1961, he was called up to the Tigers for good in June. Seeing action at short and third base, he batted a solid .256 in his rookie year. By 1962, he was in the lineup every day, mostly at the hot corner, but his versatility allowed manager Bob Scheffing to pencil him in at second or short as well.

McAuliffe’s unusual batting stance was suggested to him by Wayne Blackburn, one of his minor league hitting coaches. A left-handed hitter, he stood spread-eagled at the plate with his left knee pointed at the catcher and his right knee at the pitcher’s mound. His at-bats began with his right foot poised on his toes, and his bat held ridiculously high above his head, before McAuliffe unleashed his trademark vicious stroke. He was a classic “foot-in-the-bucket” hitter whose high leg kick hearkened back to Hall of Famer Mel Ott.

The swing generated occasional power (he hit 197 lifetime home runs), but also more than his share of strikeouts. And while not a high average hitter (he never reached .275 in any one season), his consistently high on-base percentage made him a tough out in an offensively-challenged era. And he was a slasher at the dish, a line-drive hitter whose swing didn’t result in many ground balls.

His breakout year was 1964, despite his 32 errors at shortstop. He blasted 24 home runs with an OPS of .762 and 4.2 Wins Above Replacement. Not bad for a kid who hadn’t yet turned 25.

By the following summer, he began a string of three-straight all-star appearances (including a home run in the 1965 game). His WAR from 1966-68 was 6.0, 5.1, and 5.6, respectively.

The 1967 season was a disappointing one for the Tigers. McAuliffe had by that time been switched to second base. The fate of the team went down to the final game of the year, which the Tigers needed to win or face elimination. With Detroit trailing 8-5 against the Angels at Tiger Stadium with two on and one out in the bottom of the ninth, McAuliffe hit into a 4-6-3 double-play to end his team’s season.

It was only the second double-play he hit into in 1967.

But in 1968, the Tigers won the American League pennant. McAuliffe led the team with 95 runs scored (and didn’t hit into a double-play all summer). He batted only .222 in the World Series victory over St. Louis, but did hit a home run Game Three at Tiger Stadium.

But McAuliffe’s signature moment in a Tiger uniform came on August 22 of that year. On the hill for the visiting White Sox was Tommy John. According to McAuliffe, John was “a lowball, sinker-slider (pitcher) with great control and not a great deal of velocity.” But in McAuliffe’s second at-bat, with the Tigers up, 1-0, John nearly beaned him on three straight blazing fastballs, with each pitch hurling toward the backstop.

In McAuliffe’s eyes, the Sox, who still had a theoretical chance in the race, wanted nothing better than to knock him out of commission for a week or two. McAuliffe glared back at John on the pitcher’s mound. The two exchanged verbal pleasantries, (John reportedly saying “What are you going to do about it?!”) McAuliffe rushed the mound, and the benches cleared right speedily.

In the words of Tommy John: “McAuliffe drove his knee into my left shoulder and separated it.” As a result, the pitcher missed the rest of the season. As for McAuliffe, he was suspended five games and fined the princely sum of $250.

Injuries and age began to take a toll, and within a few years McAuliffe was reduced to platoon status. He homered in the 1972 American League Championship Series, which Detroit lost to Oakland in five games. But after the 1973 season he was dealt to the Boston Red Sox for a young, relatively-unknown outfielder named Ben Oglivie.

McAuliffe hit only .210 in Beantown in 1974, and was released after the season.

He took a managerial gig with the Bristol Red Sox for 1975. But in August, with Boston’s third baseman Rico Petrocelli forced to go on the disabled list with vertigo, McAuliffe was surprisingly brought back to play. He appeared in seven games, all at third base, and collected two hits, as Boston won the American League East. McAuliffe, however, was left off the post-season roster, effectively ending his major league career.

“The game was very important to me,” McAuliffe once said. “I played as hard as I could. I always thought I gave 100 percent.”

Tiger fans couldn’t agree more.