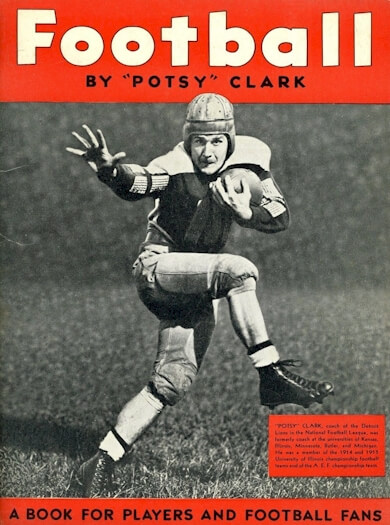

Potsy Clark was the cover boy for this football publication in the 1930s.

At some point late in the evening of Super Bowl Sunday, February 7, one team of grimy celebrants will begin planting smooches on the Vince Lombardi Trophy, a Tiffany-designed prize named after the legendary Green Bay coach. Had such a trophy existed in the 1930s, it easily could have been called the Potsy Clark Trophy. Yes, George “Potsy” Clark was that good.

According to respected football historian Bob Carroll, “In that critical era when the NFL was moving from its helter-skelter first decade to become in reality a major league, Potsy was considered the equal of such legends as Halas, Lambeau, Owen, and Flaherty. Some would have put him at the top of the list.”

Among fans with a hazy sense of history, Potsy Clark is often confused with Hall of Famer Earl “Dutch” Clark, the do-it-all tailback on Potsy’s powerful Portsmouth and Detroit squads of the 1930s.

Potsy was a likable sort who throughout his long and accomplished life enjoyed his many friendships and was a popular banquet speaker. But he was “a tough little guy,” Dutch recalled. This meant rugged practices and firm discipline.

“Potsy believed in practice,” Dutch said. “We traveled to road games by bus, so if we were going from Portsmouth to New York, say, we’d carry our football shoes, and when we came to a level field out there in the country, Potsy would stop the bus and we would get out and run signals.”

Potsy, a native of Carthage, Illinois, played football and baseball at the University of Illinois before entering the army as an artillery officer during World War I. He coached service teams to championships on both sides of the Atlantic, winning the Army-Navy title in Chicago and then the championship of the American Expeditionary Force in France. After his discharge, he coached football and baseball at Michigan Agricultural College (now Michigan State University) in the 1920-21 school year before moving on to Kansas, Butler, and then, in 1931, the football-crazy mining town of Portsmouth, Ohio. In his first season as an NFL coach, Potsy steered the Spartans to an 11-3 record, good for second place in the single-division league.

The following year, Potsy took Portsmouth into the first championship game in NFL history—an unofficial playoff famously moved indoors to a 60-yard field at Chicago Stadium because of a snowstorm. It was one of the most important games in the history of the NFL. George Halas’s Bears won, 9-0, but heightened interest in the unusual match resulted in the league splitting into two divisions and establishing a regular title game in 1933.

The Spartans finished second in 1933 before relocating to Detroit the following year to become the Lions. After opening their inaugural season in Detroit with a remarkable seven straight shutouts, Potsy’s squad dropped the last three games of the schedule—each by a field goal, including two losses to the Bears—to finish 10-3 behind Chicago.

George “Potsy” Clark

In 1935, however, the Lions captured their division with a 7-3-2 record, then dismantled the New York Giants, 26-7, in the championship game at the University of Detroit’s Dinan Field. Potsy was widely hailed as a coaching genius and even authored an instructional guidebook. One of his finds was Raymond “Buddy” Parker, who scored a touchdown in the title game and would go on to coach the great Lions teams of the 1950s.

Potsy was known as an effective teacher and administrator, one who always paid close attention to details. He also was an imaginative sort who knew how to bend the rules. In 1936, the defending NFL champs set a ground-gaining record that has yet to be matched. Operating out of the single-wing formation, in which Dutch Clark played left halfback (a.k.a. tailback) and called signals, Lions backs rushed for 2,885 yards in 12 games. This worked out to an astonishing average of 240 yards per game. Three of the league’s top six rushers that season were Lions: Dutch Clark, Ace Gutowsky, and Glenn Presnell.

Presnell later explained how Potsy’s ’36 team was able to run the ball for more yards per game than any team in pro football history. “When we practiced our signals—hut one, hut two, hut three—the linemen charged on ‘hut’ and the center snapped the ball on ‘two.’ We always hit the defense first. Potsy expected those guys to explode off their marks on ‘hut.’ And of course, the center would be hanging on to the ball a split-second longer, but enough for you to be called offside. I always attributed our good blocking to that.”

Potsy had a testy relationship with Lions owner Dick Richards, and after the 1936 season they split company. Dutch Clark took over as player-coach. Potsy went on to coach the NFL’s Brooklyn Dodgers before returning to Detroit for one last go-around in 1940 under new Lions owner Fred Mandel. By now the team was playing in Briggs Stadium, reflecting Detroit’s growing taste for pro ball. After several failed attempts in the city during the 1920s, the NFL was here to stay in the Motor City.

Remarkably, Potsy decided to walk away from pro football in November 1940, just as the sport he had helped develop during the Great Depression was finally blossoming in popularity. Looking for more stability, he accepted a position as athletic director/coach of tiny University of Grand Rapids, where his offensive line coach was future U. S. president Jerry Ford. Potsy served in the Navy during World War II and later spent a decade as AD at Nebraska and California Western. He became a successful broker in California, dying there in 1972 at age 76.

The Lions’ first coach will probably never have his bust join that of Dutch Clark in Canton. But Potsy Clark’s winning record speaks for itself. At the time he left the NFL, only Halas, Curly Lambeau, and Steve Owen—all Hall of Famers—had coached their teams to more regular-season victories.