On August 29, 1905, the lives of two people changed dramatically when one of them stepped off a train in Detroit. Both men went on to fame and success, and they were colleagues for more than a dozen years, but life was never the same for Sam Crawford after Ty Cobb arrived.

Cobb was 18 years old when he reported to the Tigers and he’d never been north of the Mason-Dixon Line. He was “green,” “raw,”—however you want to put it—he was a fish out of water. The only thing Cobb knew for certain was that he was determined to make it in the big leagues. He was going to prove that his decision to become a baseball player was wise. But Cobb was unprepared for the reception he got from his new teammates.

In 1905, 25-year old Sam Crawford was a star, one of the best baseball players in the league. He was strong, one of the premier sluggers of that era, and he was quick and a good baserunner. After manager Hughie Jennings, Crawford was the leader of the team. Cobb’s presence late in an uneventful season shook things up.

When a rookie arrived in the big leagues back then, he was not welcomed with a fruit basket. The veteran players would shun new guys, or worse. What was the worse? Try having your spikes nailed to the floor, or your bats being chopped into pieces. Most violently, new players were hazed. But this wasn’t the sort of hazing we’re used to now, the innocent type that serves as a test of the new guy’s resolve. The hazing in the deadball era was vicious. Rookies were attacked for any sign of weakness, anything that made them stand out.

The young Ty Cobb had two things that made him stand out: he was very high-strung and he was a rube from Georgia. Shortly after he pulled an Old English D wool jersey over his head, Cobb’s teammates pounced on him. His manner of speech, his ill-fitting suit, his shyness, all of it was used against Cobb. As Cobb was being greased by the mob, Crawford stood at the top of the food chain in the clubhouse. He didn’t razz Ty as much as some others (outfielder Matty McIntyre was the ringleader), but Sam did nothing to stop it.

Did I mention that three weeks before he stepped off the train in Detroit, Cobb’s father was shot and killed by his mother in Georgia? Did I mention that Ty rushed home and buried his dad and then had to endure the beginnings of his mother’s trial for murder? That all of this had just happened and here he was making his big league debut? Can you imagine a team hazing a young man who just endured that tragedy? Well, it was a different time.

Cobb later shared in his autobiography that he used the hazing to fuel his drive to be the best. “These old-timers turned me into a snarling wildcat,” he wrote.

The relationship that developed between Crawford and Cobb stamped itself on the Tigers for the 13 years they were teammates. Crawford initially saw Cobb as a curiosity, a backwards southerner who couldn’t relax. One time early in his second season, Cobb was waiting to take his turn for batting practice. McIntyre and catcher Boss Schmidt, a large man, took turns nudging Cobb aside, jumping in front of him. Cobb eventually stormed off.

Crawford came to see Ty as a threat, especially when Cobb took the starting job away from McIntyre which forced Sam to switch from right to center. Eventually Crawford and Cobb flip-flopped positions, but even though they played next to each other for many years, the temperature between them was Arctic cold.

Crawford resented Cobb’s success, his ascension to stardom, but Wahoo Sam grew to resent everything about the Georgian. He couldn’t even admire Cobb for any of the traits that Crawford himself exhibited. Crawford took the game seriously, but Cobb took it too seriously. Crawford was an aggressive player, but Cobb’s daring baserunning was to “show off.” Crawford yearned to achieve financial success, but when Cobb held out for money he was being selfish. No matter what Cobb did, Crawford wouldn’t like it. Cobb quickly realized Crawford disliked him, and let’s face it he was often an ass, so he did his share to rupture the relationship too. The teammates maintained a frosty partnership in Detroit, useful to one another, but disdainful. After about 1912, Crawford probably never said more than a dozen words to Cobb. In 1912, when Cobb was briefly suspended by the league for confronting a fan in the stands for heckling him, most of the players on the Tigers supported Ty, refusing to play until he was reinstated. Crawford did not say a word.

In 1910, when players on the Browns conspired to throw the batting crown to Nap Lajoie so Cobb wouldn’t win it, Crawford was reportedly one of the Detroit players who sent a telegram to Lajoie congratulating him.

Understandably, Cobb overshadowed Crawford, anyone who wins twelve batting titles is going to do that. But Crawford was an incredible player in his own right. Chicago outfielder Fielder Jones said of him, “None of them can hit quite as hard as Crawford. He stands up at the plate like a brick house and he hits all the pitchers, without playing favorites.”

Cobb batted in front of Crawford for most of their years in the lineup. When Cobb got on base (which he did about 45 percent of the time) he was a menace on the basepaths. Crawford learned to deal with that, he learned to concentrate at the plate with Ty bouncing off the bag, stealing a base, maybe two. The two men were on base at the same time a lot, probably as much as any other pair in history outside of Lou Whitaker and Alan Trammell (or maybe Hank Aaron and Eddie Mathews, or Craig Biggio and Jeff Bagwell). But I digress, the point is that Cobb and Crawford were on base together often and they coordinated a series of signals that helped them pull of double steals. The two men must have huddled together at some point to scheme. If Cobb was on second in front of Crawford and he kicked the bag a certain number of times, it signalled a double steal, if he whistled and kicked it meant he was stealing, and so on. The two men hated each other, but they arranged a system to cooperate on the diamond.

The rift between the two former Tigers continued after they retired from the field. In the 1940s when The Sporting News published a story about Crawford’s career, Cobb wrote a letter to a sportswriter friend who worked for the paper. In his letter, Cobb reportedly claimed that Crawford was jealous of his success, never assisted Cobb when he was a young player, and intentionally fouled off pitches when Ty was trying to steal bases. Crawford later learned of the letter and bristled. If anything the letter showed how petty Cobb could be and how serious the dislike was between the two men.

It’s been said of Cobb and Crawford that they had the worst relationship of any long-term superstar teammates in baseball history. I’m not sure about that. Jeff Kent hated the guts, the bones, and the marrow of Barry Bonds, and Bonds disregarded Kent like he did everyone. I will say this: Jeff Kent will never campaign for Barry Bonds to make the Hall of Fame, or vice versa. But Ty Cobb made sure Wahoo Sam got into the Hall.

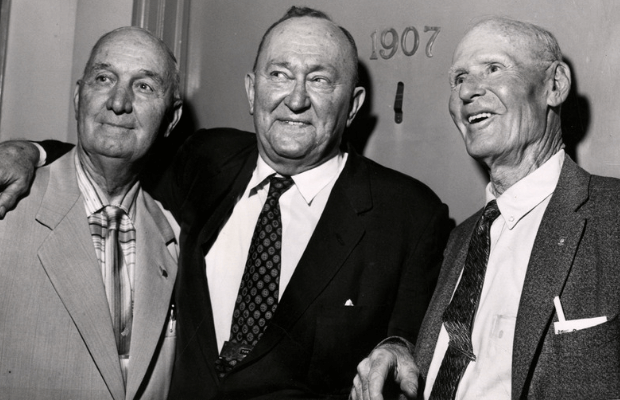

For years, Cobb wrote letters pushing for his old teammate to be elected, which Crawford was in 1957. Sam reportedly wrote a letter to Cobb thanking him for his support and when they saw each other on the porch of the Otesaga Hotel in Cooperstown for induction weekend, Wahoo Sam embraced his old teammate.