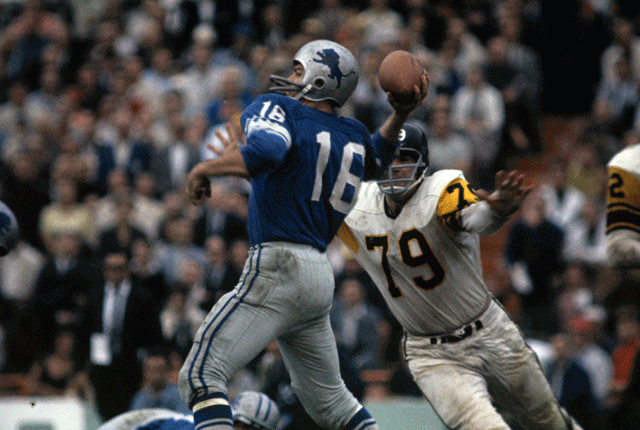

Detroit quarterback Milt Plum tosses a pass in the 1962 Playoff Bowl against Pittsburgh at the Orange Bowl in Miami.

In modern professional sports we’re used the notion of teams that finish second (or third or even fourth or fifth) making the postseason.

The NBA allows eight teams into the playoffs in each conference, regardless of what place they finish in the regular season. For decades the National Hockey League has put on a tournament-style postseason that has grown into a season of its own, a battle for the Stanley Cup. Many teams that finished lower than first place hoisted the Cup. Even Major League Baseball, the stuffed-shirt conservative William F. Buckley of the party, eventually acquiesced and added wild card teams in the 1990s. Six wild card teams have won the World Series, the most recent the 2014 San Francisco Giants. The NFL has four “wild card” teams each postseason, and on multiple occasions a wild card team has won the Super Bowl.

But there was a time in pro football when only the first place teams in each of the two divisions advanced to the playoffs. This was “THE EN-EF-EL”, as it was romanticized by the deep baritone voice of John Facenda for NFL Films.

For ten years during this era, from 1960-69, fans slapped down good money to watch the two second-place teams face each other in a meaningless game played at one of the most famous stadiums in the country.

The Detroit Lions appeared in that game three times in the 1960s. Why? Because they could never get past Vince Lombardi’s Green Bay Packers, who finished ahead of them in 1960, 1961, and again in 1962, when Detroit had what many consider one of their best teams ever. But 11-3 wasn’t good enough as the Pack won 13 games in the regular season and advanced to the NFL Championship Game. The Lions, instead, went on to Miami to play in the Playoff Bowl, the battle of second-place teams.

The Playoff Bowl was born for three reasons, one of them altruistic, one of them monetary, the other built on ego. On October 11, 1959, in Philadelphia during an Eagles/Steelers game, NFL commissioner Bert Bell died. Bell was a giant of a man, a former player, a successful businessman, and a visionary who helped build the NFL’s foundation as a media empire. One of Bell’s pet projects was the establishment of a pension for players. Not long after his death at the age of 64, plans were being made to raise money in his honor for such a purpose. Ultimately the league decided to host a postseason game the following year, some of the proceeds going to the Bert Bell Players’ Pension Fund.

That was the truly compassionate reason for what came to be known as the Playoff Bowl (but was officially called the Bert Bell Benefit Bowl). Another was the piles of cash there was to be made from television. Football is a sport that seems to have been made for the boob tube. At the dawn of the 1960s the NFL realized that their playoff format of just one title game was not enough. College football was making tons of money with several big bowl games in and around New Years’s Day. Strangely, rather than consider expanding the postseason, the NFL chose to schedule the game, a contest that came to be known as “a battle for third place” in the league.

A third reason the NFL wanted the game was to show off their product’s superiority to the fledgling American Football League, “the upstart AFL”, as they were derisively known by NFL owners. Ironically, it was the smugness of the NFL owners that helped spawn their new rival. After refusing to allow several investors into the league, those same businessmen huddled together to start the AFL. The NFL owners surmised that with only one championship game on TV they would need more opportunities to showcase their highly-skilled players.

Following the 1960 regular season when the Lions and their 7-5 record finished second to Green Bay, they headed south to Miami’s Orange Bowl to face the Cleveland Browns on January 7, 1961. It was a strange situation for both teams, seeing as nothing was on the line. Adding to the funkiness was the fact that the NFL scheduled the game for the week after their title game. It all seemed a bit anticlimactic. However, with the spectacle of NFL football on display, more than 34,000 fans filed into the Orange Bowl. The Lions, for their part, helped initiate a Playoff Bowl tradition by partying a lot in the days before the game. Several players stayed up til dawn several times during the week. Even so, the Lions squeaked out a 17-16 victory over the equally hungover Browns.

The following January the Lions defeated the Philadelphia Eagles handily 38-10 in the second Playoff Bowl, in a game that featured three touchdown connections between Lions’ quarterback Jim Ninowski (a Motown native) and wide out Gail Cogdill.

The ’62 Lions team fielded “The Fearsome Foursome” defensive line of Roger Brown, Alex Karras, Darris McCord, and Sam Williams. While the quartet reveled in punishing opposing QBs in the regular season, they had no desire to play in something called the Bert Bell Benefit Bowl. Brown played in five Playoff Bowls, adding two more with the Rams later in the decade. He was not a fan.

“I was in five of them, and to have played in it five of the 10 years it was in existence is pitiful,” Brown said.

For Brown and other african american players, there were other reasons to hate the game. In their first year in Miami, the african american players had to stay in a different hotel from their white teammates. Then something great happened.

“After practice one day, [white teammates] Jim Gibbons, Nick Pietrosante and Howard Cassady talked to [head coach] George Wilson,” Brown explained in a2011 interview with the New York Times. “They said, ‘We’re all going to go home [unless they let you stay in our hotel] because we came down here as a team, we’ll stay as a team and play as a team.’ ” The three black Lion players (Brown, Dick “Night Train” Lane, and Danny Lewis) were moved into the hotel with the rest of the team.

Brown and the Lions won the Playoff Bowl again in January of 1963, using their stifling defense to get past the Steelers for a 17-10 victory. A crowd of almost 35,000 was on hand, which was just enough to convince the NFL to keep the game in Miami. Quarterback Milt Plum and running back Kenny Webb led the Detroit offensive attack.

But that was the last time Detroit played in the Bert Bell Benefit Bowl, even though it went on for six more years. Even Vince Lombardi ended up being subjected to the game, leading his Packers down to Miami twice in between their stints winning five titles in the 1960s. But ol’ Vince didn’t like it. He called Miami a “hinky-dink” town (the AFL had a franchise there but the NFL was not in Florida yet). He also had an inventive name for the contest, he called it the “Shit Bowl.”

Over the course of a decade the Playoff Bowl raised more than one million dollars for a players’ pension fund. Still, after the NFL and AFL agreed to officially merge in 1970, the game was scrapped. The new NFL added another round of playoffs and seven postseason games was enough.

The battle for third place was over.