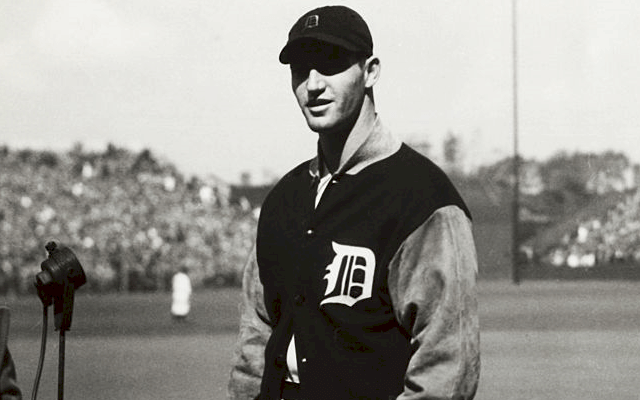

Detroit pitcher Lynwood “Schoolboy” Rowe prepares to do a radio interview during the 1934 World Series between the Tigers and Cardinals.

The following is an excerpt from Scott Ferkovich’s upcoming new book, Motor City Champs: Mickey Cochrane and the 1934-1935 Detroit Tigers.

Ever since he was a youngster growing up in the liltingly named town of El Dorado, Arkansas, Lynwood Thomas Rowe had been drawing attention because of his athletic prowess, particularly on the baseball diamond. He had always been tall and strong, but his graceful agility set him apart from others. He was born in Waco, Texas, on January 11, in either 1910 or 1912, depending on whom you believe. In the early 1920’s his family moved to El Dorado, as did so many others seeking work in the town’s oil boom of that decade. For the rest of his life, Lynwood would consider himself a Razorback.

His brush with greatness came early. In grammar school, one of his teachers was a Miss Mary Blackman, soon to become the wife of Travis Jackson, who at the time was just beginning his Hall of Fame career as a New York Giants shortstop. Much of Rowe’s early life is shrouded in hyperbolic mystery, perpetuated (perhaps even created) by sportswriters thirsty for tales of a Paul Bunyan-like figure. With Schoolboy Rowe, fact and fiction were often interchangeable.

His childhood athletic feats were the stuff of myth, and probably have some basis in fact. The exact origin of his “Schoolboy” nickname is a historical quagmire. It testifies to a sporting wunderkind who amazed onlookers with his ability to compete with, and against, players much older than himself. According to one story, apocryphal or not, he was already such a fabled pitcher (and slugger) at age 14 that he was recruited to play in a local adult church league.

One day, young Lynwood was on the mound for the Methodists, trying to protect a fragile one-run lead. Facing the Baptists’ biggest slugger, he heard a cry cascade down from a hostile fan: “Don’t let that Schoolboy beat you!” Rowe beat the Baptists, anyway, and a legend (and a nickname) was born.

Like all great high school athletes in those days, he was a multi-sport star. He was only an average student, although he did receive a prize for penmanship. When not at school or on the athletic field, Rowe could usually be found caddying at Oakhurst Golf Club or hawking newspapers on a downtown street corner. Rowe loved the competition of sports, whether it was football, basketball, or track and field. He excelled in all of them. He was even a talented golfer and boxer. One writer referred to him as a “one man All-American athletic team,” in high school. He had excellent eye-hand coordination, and was a crack bowler and pool player. The sport that Rowe loved most, however, was baseball, and the irony is that El Dorado High did not field a team. He began building his star reputation on the city’s sandlots, however, and the Detroit Tigers eventually got wind of his exploits.

They dispatched scout Eddie Goosetree to El Dorado to see what all the fuss was. Goosetree located the Rowe homestead, and knocked on the front door. When an undersized, middle-aged man opened it, and acknowledged that he was Lynwood Rowe’s father, Goosetree’s heart sank: Thomas Rowe resembled nothing so much as a bank teller. He did not look like the type of man capable of siring a progeny worthy of the legends making the rounds. In truth, Goosetree misread the Rowe patriarch, who had been a circus trapeze performer in his younger, more vigorous days. Schoolboy, for his part, always insisted that his Pop had been an architect.

Mr. Rowe told Goosetree that Lynwood most likely could be found down at the firehouse. Not expecting much, but figuring he had already made the long trip and might as well see it through, the scout headed for the firehouse. Goosetree took one look at Rowe, who was big for his age, and decided he might make good, especially since the kid should continue to grow (Rowe eventually topped out at six feet four inches, although some claim he was a bit taller.). Using the persuasive powers of a $250 bonus, Goosetree got the (supposedly) 16-year-old Lynwood to sign a Detroit Tigers contract. “Eddie wrote out the contract on the back end of the hook and ladder truck in the El Dorado fire house,” Rowe explained years later. Of course, he was not yet of legal age to put pen to anything, so the elder Rowe had to cosign the document. Schoolboy’s professional baseball odyssey was about to begin.

According to legend, he refused to report to the Fort Smith (Arkansas) Twins of the Class C Western Association. That resulted in his being suspended by Organized Baseball. Since he was still in high school, however, he was forced to hide his professional status if he wanted to continue to play extra-curricular sports. With his high school still without a baseball team, he continued to play in local leagues for the next two summers. Beginning in 1929, he wandered around in semipro baseball, in cities as far north as Utica, as west as Wichita, and as south as Bastrop, Louisiana. All the while, he was still contractually bound to the Tigers, and when he again refused their minor league assignments to Little Rock in 1929, and finally to Evansville, Indiana in 1931, he remained in a state of suspension by Organized Baseball.

One possible explanation for Rowe’s failure to report to the minors comes from J. Alva Waddell, one of his high-school coaches. The way Waddell told the story in 1934, Rowe believed “he had made a mistake casting his lot with an outfit like the Tigers, who ‘probably never would win a pennant.’ He thought he should have gotten into an organization like the New York Yankees or Philadelphia Athletics.” In a possibly self-serving account, Waddell claims to have eventually talked Rowe into sticking it out with the Detroit organization.

It sounds plausible enough. In any event, Rowe was not without an alternative; he had reportedly received a football scholarship from the University of Southern California. Whatever the reason for Rowe’s mystifying refusal to go where the Tigers sent him, we do know that he finally agreed to report to the Beaumont Exporters of the Texas League. He was the victor in the first game he pitched, hitting the go-ahead home run in the process.

Perhaps Rowe’s biggest booster was Frank Navin, who practically demanded that the young stud be called up to the Motor City in 1933. Fans in Detroit had been hearing a lot of chatter about the Schoolboy, and eagerly awaited his major league debut on April 15 that season against the White Sox at Navin Field. Using an easy pitching motion, Rowe threw a complete-game six-hit victory. Afterward, he immediately wired one of his old high-school coaches: “Dear Coach. Beat Chicago, 3 to 0. Allowed six hits. As ever, Schoolboy.” He confided to reporters, “The one ambition of my life always has been to win my first big league game.” With that now out of the way, what would he do for an encore?

Rowe had always experimented with an assortment of pitches, including a knuckleball, usually from a side-armed or “cross-fire” delivery. Beginning in 1934, Tigers’ manager Mickey Cochrane insisted he simplify and focus on his overpowering fastball. Rowe also altered his pitching motion to more of a sweeping overhand manner. With his enormous stride, Schoolboy appeared to hitters as if he were on top of them when he released the ball. Noted for always pitching in a sweatshirt under his jersey, he had pinpoint control. In time, he developed a sharp, late-breaking curveball so good that it often fooled the umpires, robbing him of strikes. It was his heater, however, that set him apart: Charlie Gehringer called it “one of the finest fastballs I ever stood behind.”

Reporters grew more and more attracted to Rowe’s eccentric personality. So did the public. Like many athletes of his time, he smoked, and his preferred meal was a thick, juicy steak. He also broke with convention, however, by ordering large plates of spinach in restaurants, a gastronomic choice that automatically pegged him as an oddball among his meat-and-potatoes teammates. Baseball players have always been a superstitious lot, and Rowe was no exception. On days that he pitched, he filled his pockets with talismans, amulets, and tokens, and the righty always made a point of picking up his glove with his left hand. Among his other good-luck charms were “a Canadian penny, some Belgian and Dutch coins, a United States ten-dollar gold piece, and a jade elephant.” Rowe also talked to the ball while on the mound, engaging in chatter meant to convince the orb of the necessity of landing in the strike zone. He called the ball his “Edna,” in honor of his girlfriend. “C’mon, Edna,” he would cajole, “we got this guy Foxx right where we want ‘em.” The ball took on a life of its own in Rowe’s mind. “Careful, now, Edna. Don’t let Ruth get those arms extended.” The fact that Rowe had a sweetheart back home was bad enough for the female throngs who stormed Navin Field on a typical ladies day. That he was serious enough about the girl to name a baseball after her…now that was doubly devastating. Rowe’s dark hair, penetrating eyes, and chiseled jawline had caused many a swoon among his admirers. Even his gold-capped front tooth, the result of a high school football injury, lent him a certain air of roguishness. Early in his major league career, there was discussion that perhaps the Tigers would try Rowe in the outfield, where they needed offensive help. Everyone knew the kid wielded a strong bat, and the temptation was there. If Babe Ruth had made the conversion from stud pitcher to slugger, could not Schoolboy do the same?