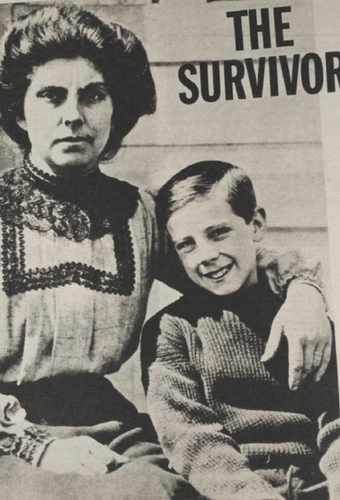

Emily Goldsmith and Frankie Goldsmith in a photo taken in Detroit in 1913.

On the evening of April 14, 1912, in the chilly waters of the north Atlantic, the passenger ship RMS Titanic struck an iceberg and quickly sunk. Of the estimated 2,224 people on board, more than 1,500 died in the frigid waters in what was the worst peacetime maritime disaster in history.

Less than a week later, while news continued to trickle in about the Titanic sinking and loss of life, the Detroit Tigers opened their new steel-and-concrete ballpark, called Navin Field. Located in the Corktown neighborhood on the corner of Michigan Avenue and Trumbull Avenue, it was a splendid new venue for the growing city’s popular baseball team. The club featured star outfielder Ty Cobb, a one-of-a-kind performer who delighted fans with his daring style of play.

Ironically, the two stories: the tragic sinking of the British passenger liner and the debut of a new baseball park in the emerging automobile capital of Detroit, would converge in the life of a remarkable young man who survived the disaster but never fully recovered from the horror of it.

“The most horrible sounds ever heard by mortal man”

Frankie Goldsmith was nine years old when he boarded the Titanic at Southampton in England with his father, mother, a friend of his father’s and a teenage son of a friend of the family. The five members of the party were all third class passengers on the maiden voyage of what was being called the “greatest ship ever constructed” and others in the shipping industry were claiming was an unsinkable vessel.

The Goldsmith’s destination was Detroit, where they had family who previously migrated to the United States. Frankie’s father, Frank Sr., was a skilled toolmaker and he carried on the ship a suitcase of custom tools and items of the trade. The Goldsmith’s planned to stay with family until Frank Sr. secured a job or opened a tool shop of his own. The lure of the American dream had them excited for the future.

Little Frankie met and played with several children his age who were also in third class. Passengers in third class slept and ate in the third class section of the ship and only were allowed to ascend to a deck that was for third class passengers. Little Frankie enjoyed the brief periods on deck observing the north Atlantic journey, but he always remembered the chance to visit the bowels of the Titanic, where he saw the dust-covered workers stoking the great furnaces of the ship.

Just before midnight on April 14, a large iceberg emerged in the path of the Titanic. There was no avoiding it. The berg carved a sharp cut into the ship, dooming her. In less than three hours the great ship would disappear beneath the cold waters, taking more than 1,500 souls to their deaths. Among them were Frank Sr., his friend, and the young 16-year old friend of the family who traveled with them. Frankie and his mother Emily were in one of the lifeboats that had been launched in the frantic moments following the ship’s collision with the iceberg. Despite the seriousness of the situation, many passengers refused to enter a lifeboat, never believing that the ship could be sunk. The death toll was skewed toward class: most third class passengers did not survive. If you were in first class you had a much better chance.

Many women and children were loaded onto lifeboats, which is where nine-year old Frankie found himself as the tragic event unfolded. “My dad reached down and patted me on the shoulder and said, ‘So long, Frankie, I’ll see you later.’ He didn’t and he may have known he wouldn’t,” Frankie wrote later in his memoir about the incident.

As it became evident that the Titanic was going to go down, thousands of people realized they were facing their fate. With their lifeboat only about 60 percent full with two crew members handling it, Frankie and his mother were paddled away from the site of the great ship. Tragically, they could hear the frantic wailing and desperation of those in the water.

“The sound of people drowning is something I cannot describe to you and neither can anyone else,” Frankie said. “It is the most dreadful sound and then there is dreadful silence that follows it.”

Another survivor, a man named Archibald Gracie, described the scene:

“…there arose to the sky the most horrible sounds ever heard by mortal man except by those of us who survived this terrible tragedy. The agonizing cries of death from over a thousand throats, the wails and groans of the suffering, the shrieks of the terror-stricken and the awful gaspings for breath of those in the last throes of drowning none of us will ever forget to our dying day. ‘Help! HELP! BOAT AHOY! BOAT AHOY!’ and ‘MY GOD! MY GOD!’ were the heart-rending cries and shrieks of men, which floated to us over the surface of the dark waters continuously for the next hour, but as time went on, growing weaker and weaker until they died out entirely.”

Eventually the screams disappeared and all that was left was a large floating debris field and the 20 lifeboats with about 700 survivors. The total capacity of the liefeboats was only 1,178, about half the number of passengers and crew of the ship.

Within a few hours, Frankie and his mother and the survivors on the other boats were rescued by the RMS Carpathia. But while he was alive, Frankie was not without fear. His mind turned to the fate of his father. Confusion about rescue efforts (some thought as many as five ships had answered the rescue call and that most passengers had been picked up) muddied the situation. An officer on the Carpathia told Frankie that his father, safe on another ship, “would probably reach New York before you do.”

But Frank Sr. was gone, a fact that young Frankie took a long time to accept. First he would spend years dealing with the horrible mental images that stayed with him from that fateful night.

Living in the shadows of Navin Field

With the patriarch of their family lost, the lives of Emily Goldsmith and Frankie Goldsmith were shattered. After a few weeks in New York recovering, the two of them were sent by train to Detroit thanks to a donation from the Salvation Army. They were greeted at the train station by their relatives. The next few years would be very difficult for Frankie.

Goldsmith felt tremendous survivors guilt, and for a long time he refused to believe that his father was dead. He clung to the idea that Frank Sr. was rescued by a passing ship and would walk through the door any day. For a long time he had a difficult time communicating to people and he suffered nightmares.

Emily and Frankie eventually settled in a small house on Trumbull Avenue, only a short distance from Navin Field. But the proximity proved to be painful. When the Tigers did something on the field to rouse the home crowd, the resulting roar terrified Frankie.

“[Navin Field] was a scary place to me for a long time,” Frankie wrote years later. “Every time I heard the collected voices of the crowd cheering I was reminded of the screams from [the people] who were in that water.”

Despite the lure of the ballpark, Frankie never attended a game at Navin Field and never took his children there. He could walk past Navin Field (later Briggs Stadium during his years in Detroit) but he wouldn’t go near it when a game was being played.

When his mother remarried and her new husband decided to move into the Corktown neighborhood, Frank Jr. fled out of the house and lived with relatives rather than stay near Navin Field.

In 1926 Frankie got married. He remained in Detroit through World War II, when he worked as a civilian photographer for the U.S. Army Air Corps. He later settled in Ohio and opened a photography shop. By the little I can find about his mid-life, Frankie eventually overcame the horror of the Titanic disaster and enjoyed raising three sons, one of whom was named Frank II.

Goldsmith died in Florida on January 27, 1982, at the age of 79. His memories of the Titanic and his thoughts about living his early life without a father were too painful to express in words, but he left behind a diary and notes that he’d written throughout his life. One of his sons published them under his name as Echoes In the Night: Memories of a Titanic Survivor in 1991. In accordance to his wishes, Frank Jr.’s ashes were scattered over the area where the Titanic had sank, reuniting him with his father.

One reply on “A Titanic survivor: The boy who was terrified by Navin Field in Detroit“

Comments are closed.